An Antitrust Paradox: The Conservative Reaction to ESG Investing

Robert Bork Jr.’s cynical embrace of antitrust activism is helping fuel the latest culture war.

*This post was previously only available for paid subscribers, but due to unforeseen circumstances I have not been able to make my usual weekly post and have decided to instead release this one for all users. If you want more content like this or simply want to support my work, please consider a paid subscription. In the meantime, enjoy!*

For decades, Robert Bork’s The Antitrust Paradox has been the seminal text for conservative antitrust. According to Bork, antitrust law as it stood in the 1970s was pursuing too many contradictory goals at the same time, making for a jurisprudence that was both legally inconsistent and harmful to consumers. As a remedy, Bork recommended the application of the consumer welfare standard, a doctrine which asserts that a firm’s conduct should only be ruled unlawful if its result or intent is to reduce the welfare of consumers, typically by increasing the price or decreasing the quality of a good or service in a given market. Bork thought the circumstances under which this could happen were narrow, adopting George Stigler’s famous dictum that “competition is a tough weed, not a delicate flower.” Bork contended that entry into most markets was relatively easy and that most oligopolies were incapable of sustained collusion. The application of Bork’s ideology led to increasingly lax antitrust enforcement and a stunning rate of concentration in market after market. Only recently has Bork’s dominance been challenged by champions of more stringent antitrust enforcement, including FTC Chairwoman Lina Khan and DOJ Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter.

The most vocal defender of Robert Bork’s legacy today is his son, Robert Bork Jr., who serves as president of the Antitrust Education Project, which aims to teach “a new generation of Americans about the success of the centerpiece antitrust concept, the Consumer Welfare Standard.” That’s why it’s bizarre that Bork Jr. has spent the last year publishing a series of op-eds arguing that asset managers’ adoption of ESG investing strategies somehow constitutes an antitrust violation. His tortured reasoning on this issue marks a revival of all the inconsistencies his father fought to banish from antitrust. This week’s post will be about the contradictions in the conservative case against ESG.

In his crusade against ESG, Bork Jr. adopts several arguments that strangely interlock with and contradict one another. First, he argues that by adopting ESG investing strategies, asset managers are not fulfilling their fiduciary duty to their investors. By paying undue attention to the risks posed by climate change, these firms cost their investors money without being upfront about what they’re doing. In an article called, “How ESG will hurt your retirement,” Bork Jr., explains:

In the last five years, according to Terrence Keeley, former BlackRock senior executive, global ESG funds have underperformed the broader market with an average return of 6.3% compared with an 8.9% return for non-ESG funds. An investor who put $10,000 into an average global ESG fund in 2017 would have about $13,500 today, compared to $15,250 for someone who invested in the broader market.

This sounds pretty damning, so I figure I’d check the source. The source in this case is a Wall Street Journal op-ed piece written by Terrence Keeley, author of the book SUSTAINABLE: Moving Beyond ESG to Impact Investing. In the op-ed, Keeley simply asserts these figures, providing no source. I tried to find any study backing Keeley’s claim and was unsuccessful. But I am not alone. Keeley’s op-ed is cited as evidence of ESG’s failures by the American Energy Alliance, Reason Magazine, and a letter addressed to members of Congress signed by 27 state attorneys general, all of which repeat the same statistic as Bork Jr.! (At first, I thought Keeley may be citing figures from his book, but it does not seem so. In a post for the American Enterprise Institute where he repeatedly cites his book, when sourcing these figures he cites his own op-ed piece.)

If Keeley’s claim were true, it could somewhat help Bork’s case. After all, investors are consumers of the financial products being sold to them, so perhaps the consumer welfare standard could be applied here. However, analyses that are more transparent than Keeley’s suggest that adopting ESG strategies has not hurt the performance of corporations or the funds that invest in them. For instance, an analysis by S&P Global found that the ESG variant of the S&P 500, slightly outperformed the regular S&P 500 since the former’s creation in 2019.

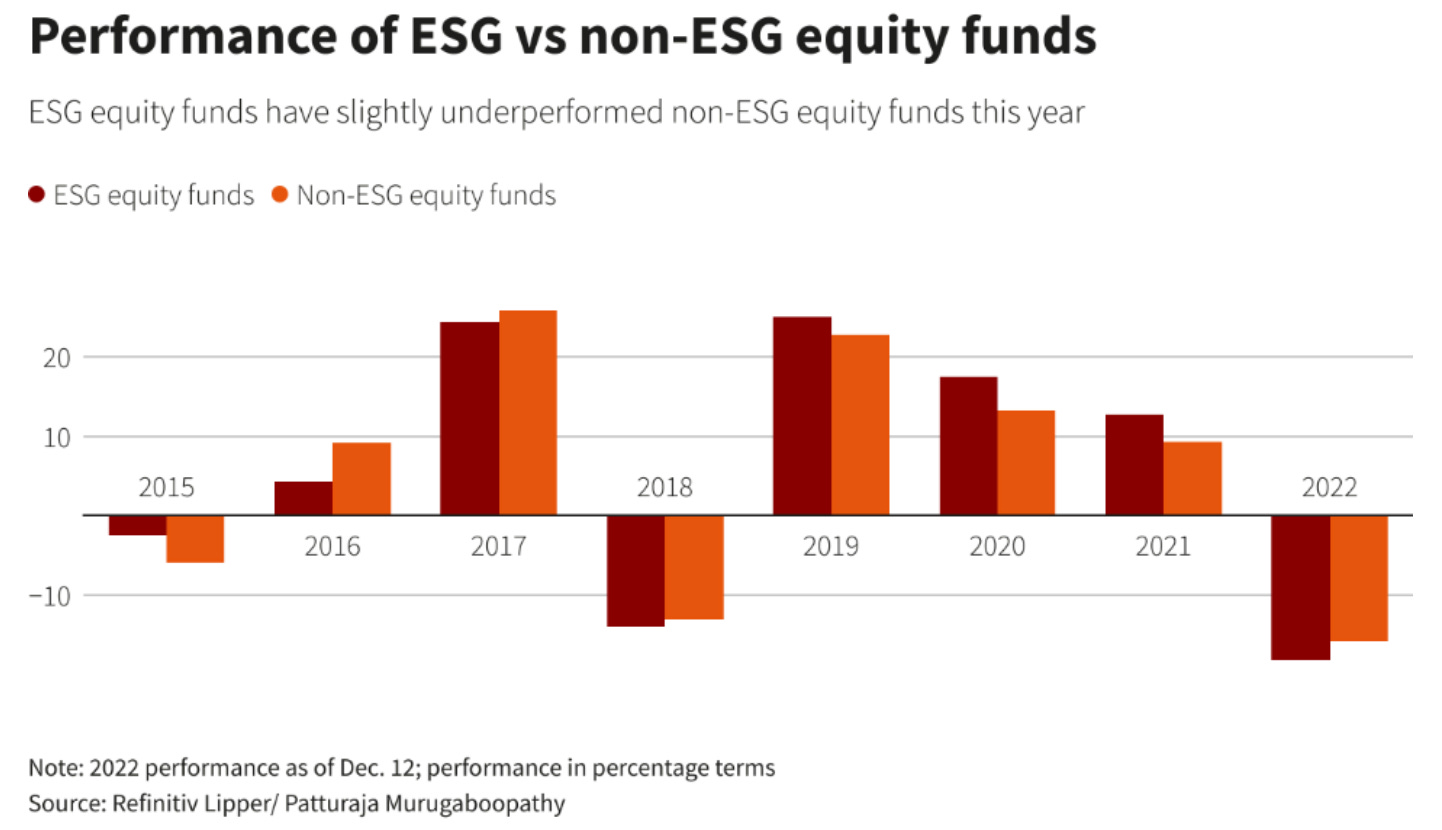

A more detailed analysis by Charles Schwab agrees, finding that “ESG funds have done as well as other funds over time.” SS&C Technologies concurs, finding that ESG equity funds perform similarly to their non-ESG counterparts, overperforming in 2019-2021, though underperforming in 2022. They conclude with an analysis of the existing research:

The most comprehensive meta-study of more than 1,000 research articles published between 2015-2020 reports 58% of those papers find a positive link between ESG and investment performance, while only 8% show a negative relationship, with the remaining 34% being neutral or mixed results.

Even the studies cited by opponents of ESG tend to confirm this conclusion. Bork approvingly cites the anti-ESG analysis of Aswath Damodaran, while failing to acknowledge Damodaran’s widely cited paper co-authored with Bradford Cornell which concludes that:

In summary, the evidence that markets reward companies for being “good” is weak to non-existent, which can either be taken to mean that markets are rationally assessing ESG actions and finding that they have little effect on value or that markets are short sighted and are not incorporating the long-term value increases associated with being more socially conscious. Either conclusion is not promising for ESG advocates; the first undercuts their central thesis that being good translates into doing well, and the second makes it less likely that managers will invest more in ESG, because they will realize few tangible benefits in the market today.

The Wall Street Journal uses this conclusion to argue that firms that make ESG announcements don’t do very well or much good. However, you could also conclude that these firms don’t do very bad or much harm. They just perform about the same as normal non-ESG firms.

So, the vast majority of existing evidence suggests that firms that commit to ESG strategies are not shirking their fiduciary duty. In fact, promoting ESG seems to have no significant long-term impact on returns. This cripples the fiduciary case against ESG but could strengthen the antitrust case. After all, it’s difficult to argue that asset managers are participating in anti-competitive conduct just to drive their returns below the rates of competitors. Sticking with that bargain would amount to corporate suicide. After all, entry into the financial services market is only getting easier and investors are free to choose between ESG and non-ESG offerings. If anything, it would appear that the emergence of ESG funds marks an improvement in consumer welfare by increasing the diversity of offerings available to investors while not foreclosing other options.

But what if commitments to ESG did foreclose other investing options? What if the goal of ESG investing was to swallow the entire market, crippling dissidents and leaving consumers with no choice but to invest in the ESG conglomerate. This is another tact taken by Bork Jr. and it is rife with problems.

First, because ESG funds generally perform no worse than non-ESG funds, it’s difficult to argue that they are engaged in a predatory boycott, accepting losses to impose greater losses on rivals they wish to crush. The far more reasonable explanation for ESG fund conduct is that their managers believe that green energy is the future and that fossil fuels are not. Bork Jr. can argue that this is a fad or bad analysis —and who knows, maybe he’s right— but who’s he to tell other people how to invest their money. Entry into the asset management business is relatively inexpensive, and every firm currently sells a bevy of non-ESG financial products.

Second, there is no evidence that the alleged victim of such collusion —in this case dirty energy companies or any other firms not adhering to ESG standards— has been seriously harmed by the adoption by some asset managers of ESG standards. Bork Jr. alleges that:

These [ESG-promoting] executives are raising the price Americans pay for gasoline and home heating, while contributing to the unreliability of the electric grid by issuing self-ennobling Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) directives that force companies to reduce gas exploration and production in the name of climate change.

He also wades into the conspiratorial:

Although the media won't admit it, this market abuse is now causing pain. ESG's emphasis on investments in Big Tech companies and de-emphasis on oil and gas companies means that millions of small investors are seeing red down arrows in their pension statements. But restricting energy investments conversely means that Wall Street firms and the billionaires who control them are making huge profits on their remaining conventional energy investments.

But Bork Jr. never provides any evidence for these claims. Capital markets are deep and diverse and dirty energy companies have access to numerous sources of investment capital. They also have been earning record profits which they could dip into to finance more production if they so wished. Lastly, oil companies in particular have experienced record stock growth and market capitalizations in the last few years. The supposed connection between ESG investment and energy prices is also entirely unsubstantiated.

Third, in order to be unlawful, any group boycott would need to be done for demonstrable commercial reasons, rather than social ones. As The Antitrust Attorney Blog explains,

if defendants’ conduct is not commercially motivated activity, it is not subject to group-boycott antitrust liability. This is an established exception, with a well-developed doctrine.

So if ESG investors were to argue they were taking part in a group boycott, but prove that their motivations were strictly social, then the antitrust case against them falls apart. By harping about their alleged low returns relative to non-ESG funds, Bork Jr. is helping them build such a defense

Lastly, we’ve yet to discuss the elephant in the room. Is there even any evidence of a group boycott to begin with? So far, the evidence is much slimmer than the deluge of headlines suggests. Some unsophisticated commentators will point to the fact that a declining ESG score can get you removed from ESG index funds, but that’s not a group boycott. After all, when Tesla was booted off the S&P ESG 500 Index, it still remained on the S&P 500. That’s no boycott at all. Besides, index funds, by their very nature, exclude some firms to the benefit of others. A more promising line of argument is that oil and gas companies are the victims of a boycott because of the E[nvironmental] in ESG. But this isn’t true either. Year after year, petroleum-spilling, fossil-fuel-burning ExxonMobil maintains a good ESG rating. The only potential victim of such a boycott is the ill-defined market of those-who-don’t-meet-ESG-standards. But clearly, targeting these firms with a predatory boycott would never work; as noted above, these firms have plenty of access to capital. The original Bork understood that these sorts of far fetched boycott theories are highly implausible in reality:

The boycotting group would have to control 80 or 90 percent of the market to have any chance of success, and the losses the group accepts as well as inflicts through disruption of the distribution pattern must not only be substantial but must be proportionately larger for the victim than for the group if the victim’s reserves are to be exhausted before the group begins to suffer defections. These preconditions for successful predation by naked boycotts reflect trade association politics and evanescent bravado more than they do serious threats to competition.

Still, the elder Bork held that“[S]ince such behavior carries no possible benefit to consumers, the law is probably correct in outlawing all naked boycotts, regardless of their prospects for success.” But this is a far cry from the paranoid ravings of his son, who refuses to cite any sort of applicable or relevant legal precedent in any of his anti-ESG screeds.

Bork Jr. provides little evidence in favor of his group-boycott hypothesis. He’ll often use sweeping language, invoking “a cartel of left-wing NGOs, blue state pension funds, several asset managers, and two firms that control almost the entire proxy advisory market, holding corporations hostage” but he provides little on specifics. Bork Jr. entertains two primary theories for the enforcement mechanisms of the ESG cartel. The first theory is that by controlling enough seats on corporate boards, asset managers can force their ESG agenda onto the firms they invest in:

The top three asset managers alone cast about one-quarter of votes at S&P companies’ shareholder meetings. And the causes pushed by this ESG cartel range from defunding existing fossil fuel projects and mandating support for abortion rights, to the discouragement of donations to free market trade groups and Republican political candidates. Regardless of your politics, this is economic power being used to curtail the First Amendment.

However, there is scant evidence for this position, and Bork never provides any. Sure, the problem of common ownership —the same firm owning stakes in competing firms— is a valid antitrust concern, but that problem is actually ignored by Bork Jr., who is instead contending that the relatively small ownership shares of asset managers across several S&P 500 firms pose some sort of oligopoly problem. It’s an argument both him, under usual circumstances, and his father would never tolerate. Nor is there any evidence for it. A 2020 Morning Star analysis found that BlackRock had voted against climate-friendly shareholder proposals 80 percent of the time. This explains why ESG-labeled firms do not appear to behave better than their non-ESG counterparts. As Sanjai Baghat points out in the Harvard Business Review:

Researchers at Columbia University and London School of Economics compared the ESG record of U.S. companies in 147 ESG fund portfolios and that of U.S. companies in 2,428 non-ESG portfolios. They found that the companies in the ESG portfolios had worse compliance record for both labor and environmental rules. They also found that companies added to ESG portfolios did not subsequently improve compliance with labor or environmental regulations.

That’s right, ESG has done little to change firm behavior. Even scholars Bork Jr. respects note this. A part of Damodaran’s study, ignored by Bork Jr., notes that ESG has failed to alter firm behavior; Damodaran attributes this to ESG’s “overreliance on divestment rather than investment.” Even the extent of ESG asset managers’ divestment has been non-committal; most are not on track to meet their pledged climate goals. That shouldn’t be surprising considering that BlackRock still holds nearly $260 billion in fossil fuel stocks.

Bork Jr.’s second theory for how the ESG cartel works is more nuanced:

The green agenda of this ESG climate cartel is driven by powerful corporate and financial networks like the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, which includes networks of institutional investors, big banks, and money managers. One of the money manager networks, Climate Action 100+, has almost $70 trillion of assets under their management. BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street are the largest shareholders in more than 90% of the S&P 500. They can cast a combined vote share of 25% in S&P director elections. The ability to eject directors gives asset managers the power to force corporations to adopt “net zero” carbon emissions by 2050, whatever the cost to investors, workers, or consumers. Thus, every investor in a fund signed on to Climate Action 100+ is pushing this agenda whether the fund is labeled that way or not.

According to this theory, market power is exercised against investors, rather than firms, through alliances like Climate Action 100+, the Net Zero Assets Manager Initiative, and other third-party entities that promote green objectives like “the goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner” or “engaging companies on improving climate change governance, cutting emissions and strengthening climate-related financial disclosures, in order to create long-term shareholder value.”

Asset managers’ entry into these initiatives is voluntary of course, and since the commitments are to vague non-commercial goals, it is difficult to treat these actions as illegally collusive in an antitrust context. Otherwise, every trade organization, business publication, and non-profit organization that lobbies firms would be in violation of the law. Nobody seriously thinks PETA is an antitrust scofflaw for lobbying several competing firms to take actions against animal cruelty.

Differentiating the ESG case from a typical instance where firms engage with an advocacy organization requires a heavy burden of proof, especially because of the First Amendment considerations entangled with litigation over what an organization can say to its members.

To prove that asset managers engaged in an antitrust violation, prosecutors would want very strong evidence, ideally documents from the defendant firms, that explain the illegal intent behind their conduct or its anticompetitive effects. So far, no such documents have come to light, and there’s no evidence to suggest they exist, though a number of different entities are trying to find them—acting on political pretexts or the previously proven baseless theory that asset managers are somehow violating their fiduciary duty by embracing ESG. For instance, in March of last year, twenty-one state attorneys general sent a warning to dozens of asset managers, threatening them with increased scrutiny if they engaged in ESG partnerships. The House Judiciary Committee has gone further, issuing subpoenas to non-profit organizations, in search of evidence of collusion. One organization, As You Sow, advises firms on behalf of shareholders on how to clean up their investment portfolios. Only one ironic shred of evidence of possible collusion has emerged from all these subpoenas, and it is noted in the above-mentioned letter. I’ll quote in full:

As You Sow is also pushing three companies to stop using Vanguard as the default plan for their employee 401(k) accounts, claiming that Vanguard funds “invest significantly in fossil fuel companies.”64 As You Sow has brought three resolutions targeting Vanguard specifically without any resolutions related to the other members of the “Big Three.” Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that Vanguard withdrew from the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative in early December 2022—the same month that all three resolutions were filed. Asset managers voting for the exclusion of one of their competitors has clear antitrust implications.

In other words, the only potential victim of the alleged ESG cartel is Vanguard, the second largest asset manager in the world, which was potentially punished by a single non-profit for leaving. The existing evidence is only circumstantial. The AGs still need to do the heavy lifting of proving that the other asset managers coordinated this outcome in order for it to be treated as the sort of naked boycott that can be ruled illegal without any sort of economic evidence.

However, making the case that poor little Vanguard is being persecuted by “the elite” is so laughable that Bork Jr. can’t use it in all of his advocacy pieces. He needs to paint the victims of ESG to be consumers, investors, and retirees, lack of evidence be damned. This leads us to the last of Bork Jr.’s arguments, which is really more of a cry than a reasoned point:

For an administration that purports to be a zealous enforcer of antitrust laws, it somehow overlooks the ESG cartel’s energy squeeze as an obvious violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act, which forbids conspiracies for the “restraint of trade or commerce.” The powerful investment firms driving this movement are engaged in a public violation of federal law, which prohibits companies from colluding on group boycotts or conspiring to restrain goods. They also disregard the bedrock principle of antitrust law, the Consumer Welfare Standard.

As we’ve outlined, the reason the “ESG cartel’s energy squeeze” is overlooked is that it does not appear to exist. Bork Jr., whose raison d'être is to gripe about increased antitrust enforcement, is left crying hypocrisy, attributing antitrust enforcers’ oversight to “populist delusions” or wokeness. In fact, Biden’s enforcers are just serious about antitrust law, and don’t take Bork Jr.’s disingenuous whining to amount to evidence of a conspiracy. Lina Khan, Biden’s FTC chair, has repeatedly noted that ESG excuses will not exempt firms from antitrust enforcement.

Let’s take a moment to summarize. ESG has had no significant impact on either fund returns or firms’ climate performance. In this respect, proponents of ESG are wrong; it simply does not seem capable of addressing the problems in its sights. However, ESG does no harm either. It doesn’t reduce investor returns, bankrupt retirees, or starve the oil industry of cash. For the culture war, this is a win-win. Corporations can costlessly pretend as if they’re doing something good for the world, and conservatives can pretend that they’re taking on some big evil plot formulated by “the elites” to ruin everything. These are the kind of semi-populist fights that Robert Bork Jr. can relish. Since his organizations have been on the payroll of Apple and Google for years, he’s often branded a corporate stooge, watering down antitrust laws for his Big Tech funders, but now he can pretend to be fighting the powerful albeit in a meaningless battle.

Bork Jr. has long been a conservative ideologue, but wading into the culture war using his antitrust bona fides as a weapon has him tripping over himself with contradictions. While arguing that asset managers are colluding to destroy oil as part of their woke agenda, he’ll later contend that this is actually all part of their strategy to boost the value of their stocks in oil companies. This begs another question: how could these asset managers be divesting from oil and gas if they’re invested so heavily in them? Bork Jr. gripes at antitrust scrutiny of a recent ExxonMobil acquisition because it “go[es] against the ESG grain,” perhaps blissfully unaware of Exxon’s presence in a ton of ESG funds. He’ll argue that asset managers are shirking their fiduciary duty in supporting ESG requirements, but then ignores the vast literature (including by authors he cites) that he’s incorrect. He’ll argue that ESG funds underperform, but if that were true, how could they be engaging in (and maintaining!) a collusive plot to goose their returns? None of it makes sense, and it’s not supposed to. Readers are just supposed to grasp onto whichever theory feels right and speculate the evidence for it into existence.

Asset managers do pose several risks to our economic fortunes. They have been investing American pension funds heavily into job-killing private equity companies. Their significant ownership stakes across so many companies creates both frequent antitrust problems and conflicts of interest. Asset managers also promote financial instability through their concentration of resources and risky investing strategies. For a more thorough discussion of the negative implications of large asset managers, I highly recommend this working paper from the American Economic Liberties Project. There are serious problems with how our savings are handled by large asset managers, but the problems are not that the fund managers are too woke, too environmentally friendly, or too nice to workers.

If the WSJ editorial page didn't have lies and bad-faith arguments ... they'd cease to exist.

The idea today firms have a "fiduciary duty" to their investors is an often repeated canard by conservatives and it is false. Why would we want maximum profits for shareholders anyway? Shareholders are not productive.