The American inflation rate has been declining from its peak of 9.1% for over a year. It is now down to 3.2% and some economists are wondering if the news is too good to be true. The biggest stir this week was caused by Larry Summers who shared a graph suggesting that inflation could soon pick up once again. The graph, pictured below, shows the consumer price index (CPI) repeating the pattern it followed in the 1970s. If that pattern holds, we can expect higher inflation coming soon.

Comparing Inflation from 1966-1982 to Inflation from 2013 to 2023

Source: Larry Summers

Thankfully, there is no good reason to expect this pattern to hold. The graph is plagued with several problems, many of which have already been pointed out by market analyst Jim Bianco who branded the image a “chart crime”. He points out that the two lines Summers plots use different scales, making them look misleadingly close together. Additionally, he notes that the CPI was calculated using significantly different methodologies across these periods. The latter point should be well known to Summers since he himself co-authored a paper demonstrating just what a difference these methodological changes make. Once we adjust for these shortcomings, we don’t appear to be following the course of the 1970s after all.

Source: Jim Bianco, citing a paper co-authored by Summers himself

Besides, the inflation of the 1970s was quite different from the one we have been experiencing. Paul Krugman made the most devastating point in his NYT column: the inflation of the 1970s was brought down with a severe rise in unemployment; the inflation of 2020-22 has been reduced alongside record low unemployment figures. But that’s only the tip of the iceberg. The inflationary periods of the 1970s were primarily caused by food price shocks, OPEC oil embargoes, and the end of Nixon's wage and price controls (See Blinder and Rudd 2013). The inflation of the mid-1970s temporarily came down after supply shocks dissipated, despite the Federal Reserve’s and Gerald Ford’s vacillations on monetary and fiscal policy respectively. But inflation took off again beginning in 1978 and would not be crushed until Paul Volcker’s Federal Reserve embraced an extremely tight monetary policy, driving the unemployment rate north of 7 percent for more than four years.

Summers' proposed solution follows in Volcker’s tradition. In a 2021 speech at the London School of Economics, Summers argued that to get inflation back down to the Fed’s 2 percent target:

“We need five years of unemployment above 5 percent to contain inflation—in other words, we need two years of 7.5 percent unemployment or five years of 6 percent unemployment or one year of 10 percent unemployment,”

However, the bout of inflation we’ve been dealing with is quite different. Its proximate cause was the reopening of the economy after the pandemic. Consumers were eager to spend after being locked down for over a year, less sensitive to prices than they normally would be, and businesses were facing severe bottlenecks due to crowded ports, a shortage of truckers, and continuing lockdowns in China. The debate over how to stop inflation split into two camps. The first, which included Summers and much of the center-left, argued that demand needed to be brought under control through tight monetary policy, pointing to the rapid expansion of the M2 money supply, the trillions of dollars of fiscal stimulus distributed during the pandemic, and rising wages. With hindsight, it is clear that this position was mostly wrong. The growth rate of consumer spending initially surged alongside the reopening, but has since continued to increase at a near-constant rate since 2021 while inflation has subsided.

Personal Consumption Expenditure (2013-Present)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The second camp in the debate argued that fixing our supply chains and overcoming the shocks to our economy caused by the pandemic would slow inflation, pointing out that corporate profits were surging during the reopening and disincentivizing corporate monopolies from fixing supply chain bottlenecks. This argument was instantly maligned by Summers and the center-left who argued that the hypothesis that corporations had gotten “more greedy” was outlandish. But, that was a strawman. Of course, the economic reopening did not make corporations more greedy, it just permitted them to get away with higher markups than they typically could, as several corporate executives bragged on their earnings calls.

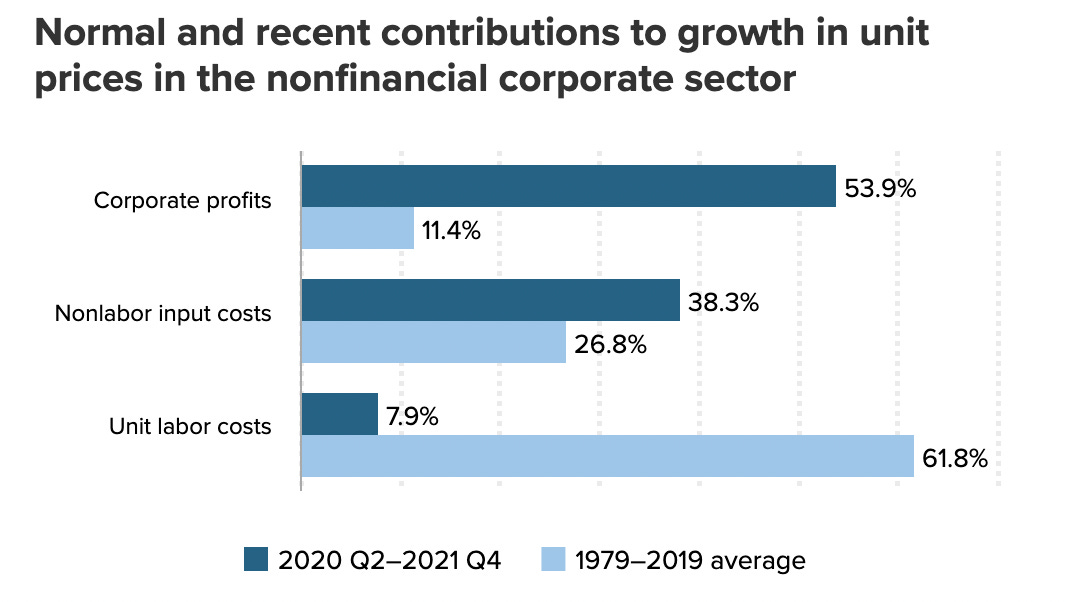

This position was also backed up by economists who bothered to treat the sources of inflation as an empirical question, rather than a dogmatic exercise. An April 2022 analysis by the Economic Policy Institute found that 54% of the inflation from between Q2 2020 and Q4 2021 could be attributed to rising corporate profits rather than increased labor or input costs. Lest you think this view is confined to a progressive economic think tank, the Kansas City Fed, hardly a bastion of progressivism, also found that nearly 60% of inflation could be attributed to corporate profits. This doesn’t necessarily mean that corporations were just price-gouging (though some surely were). Some may have been raising their prices merely in anticipation of further inflation that would drive up their costs. But these rising markups in themselves are evidence of market power that can be addressed with far more surgical economic interventions than interest rate hikes.

Source: Economic Policy Institute

Economists like Summers have been so wrong on the current disinflation for the same reason they were able to correctly predict inflation in the first place: their reliance on the Phillips Curve. The Phillips Curve is a staple of Keynesian economics which contends that the rate of unemployment and the rate of inflation are inversely related. Thus, when inflation is high, central bankers should raise interest rates, creating slack in the labor market that drives down employment, wages, and demand, thereby reducing pricing pressure.

But the Phillips curve has not looked like much of a curve since the 1960s. It’s since become a cloud of various combinations of inflation and unemployment. The reasons for this are multifaceted as a lot has changed since the sixties. The natural rate of unemployment has fallen with slowing labor productivity growth, global supply chains now more frequently have outsized impacts on prices but not employment (as we are currently seeing), and fiscal policy has played a greater role in stabilizing the macroeconomy. Unfortunately, economists’ attachment to their models can sometimes be greater than their attachment to reality.

The Phillips Curve Since 1970

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

The Fed’s raising of interest rates has likely played some role in reducing inflation, both by tightening the labor market (and thus driving down wage growth) and by reducing demand, and with it the size of corporate markups. But there are surely more targeted ways to reduce corporate markups that do not risk plunging the economy into recession.

Those who have spent the last year shouting that unemployment needs to rise for inflation to fall have now retreated into two new positions. One is to insist that inflation is far from over, which could be true. After all, who knows what supply shocks might hit us in the next twelve months. But the current evidence for a resurgence of inflation is as weak as Summers’ graph. The second position is denial. Many have simply refused to seriously reflect on the shortcomings of their predictions and instead assure the world that everyone else’s predictions were bad too. That position was recently taken up by Noah Smith, founder of the blog Noahpinion, who tauntingly tweeted:

“How many of the people who are blasting macroeconomics for thinking that bringing down inflation would raise unemployment were shouting a year ago about how the Fed was going to cause a recession”

While it’s true that many commentators have put out warnings that over-aggressive monetary tightness could provoke a recession —hardly a novel theory— it has not yet happened. The economy has prospered despite the Fed’s actions thanks to the Biden administration’s fiscal stimulus, strong consumer spending, and high domestic investment. Despite their intentions, the center left has failed to throw the economy into recession. So far, they have not reckoned with the costs they were willing to impose on workers, but allow us to.

Unemployment is at 3.8%. Black unemployment has hit record lows. Prime age labor force participation is at 20-year highs. And wages are rising quickly for the lowest quintile of the workforce. Yet some people have spent the last several months arguing that we should throw all of that away to vanquish an inflation that would have gone away anyhow.

Thank you for reading! Please subscribe and share if you enjoyed this post.

Larry Summers is a plague upon humanity. "Graphgate" is only one of his many crimes in support of the oligarchy.