Is The Laffer Curve Making Another Comeback?

Egged on by Art Laffer, Trump is pondering another corporate tax cut. We break down the Laffer curve and the long revisionist economic history supporting it.

This week it has been reported that Donald Trump is considering lowering the corporate tax rate to 15% if he wins a second term in the White House. One of the figures pushing for this behind the scenes is Art Laffer, a right-wing economist and Trump adviser who was awarded the presidential medal of freedom by Trump in 2019. His name also graces the (in)famous Laffer curve, which will undoubtedly be used to justify any future Trump tax cuts. This curve is the subject of today’s post.

Source: Investopedia

The Laffer curve begins with a simple proposition. If the government imposed a 0% tax rate, you would pay nothing in taxes. Likewise, if the government imposed a 100% tax rate, you wouldn’t work, and thus would pay nothing in taxes. It’s hard to argue with that. It’s the middle of the curve that courts controversy. At some tax rate between 0 and 100, government revenues are maximized. If taxes are so excessively high that society is situated to the right of that maximum on the curve, governments can actually gain revenue by cutting taxes!

Technically, there is not one Laffer curve, but many. The revenue-maximizing corporate tax rate is surely different from the revenue-maximizing highest marginal tax rate which is also different from the revenue-maximizing tax rate on the middle class. Proponents of the Laffer curve tend to focus on the tax rates of corporations and the wealthy since they have much more freedom to work less and withhold investment. It does not appear that the middle class has ever been taxed anywhere near the revenue-maximizing rate. Nor would we want to tax them at that level, which would likely be incredibly high. After all, you can tax a blue collar worker at an exorbitant rate, but he’ll almost surely keep working; he’s got a family to feed. An analysis by Emmanuel Saez has shown that only the top 1% of income earners demonstrate significant behavioral changes in response to tax changes. But in popular imagination, the Laffer curve is one curve and has been indiscriminately used to justify all sorts of tax cuts.

When out to dinner with Wall Street Journal writer Jude Wanniski, Laffer sketched this curve on a napkin and in 1978 Wanniski published the idea. Ever since then, a wide variety of tax cuts have been alleged to “pay for themselves” because of the logic of the Laffer curve. In fact, a whole revisionist history has sprung up arguing that nearly every tax cut of the twentieth century increased government revenues in some way. We’re going to dive into that history.

The Harding-Coolidge Cuts

The earliest historical example recounted today is the series of tax cuts between 1921 and 1926 that shrunk the top marginal tax rate from 73 to 25 percent. Taken together, these are still some of the largest tax cuts in American history. Think tanks like the Cato Institute are quick to point out that “as top tax rates were cut, tax revenues and the share of taxes paid by high‐income taxpayers soared.” But this is only half true. Tax receipts from the rich fell immediately after the top marginal tax rate shrunk from 73% to 58% in 1922. They fell again when the top marginal rate decreased further to 46% in 1924. The taxes paid by the richest tax bracket (those earning more than $100,000 per year, $1.6 million in today’s dollars) did not actually increase right away. It took all the way until 1926, after the final tax cut that reduced the top marginal rate to 25%, for tax receipts to rise. (For those in the next-richest bracket, receipts did not rise until 1928).

Source: Cato Institute

What the Cato Institute does not disclose is just what a small fraction of Americans these top earners comprised. Only 3,694 people earned more than $100,000 in 1920, making them among the top 0.05% of America’s earners. And over half of that narrow band was not even impacted by the top marginal tax rate until 1926. (Before that year the top marginal rate applied to annual incomes in excess of $200,000). How strange that the Laffer curve only appears to apply to such a tiny sliver of people. However, it is not even clear that the Laffer curve applied to these few thousands. The number of people in the top tax bracket grew significantly throughout the 1920s due to the vast rise in income inequality that decade. It’s not particularly surprising that the income tax receipts of the rich (or their share of total taxes paid) would rise when their number and their incomes are growing so much more quickly than everyone else’s. Laffer (and his supporters) never break down whether this income growth for the wealthy is the result of economic growth, increasing rents, or an increasing capital share of income.

Source: US Treasury, “Statistics of Income: 1920”

Furthermore, there is no evidence that the lower rate is what compelled the rich to begin paying their taxes, or that it is responsible for the great majority of the economic growth in the 1920s. In 1924, to get one of his tax cuts past progressive Republicans, President Coolidge introduced a new provision that made all federal tax returns public. The rich were shamed in the nation’s newspapers as cheats, and some of the ultra-wealthy could have been motivated by this to abuse the tax system a bit less to save their public image. We must also note that the economic growth of the 1920s was only marginally impacted by tax cuts: mass production and new technologies were much more important. This will be a trend going forward: instead of crediting tax cuts with marginal increases in the growth rate (which would still require substantiation), Laffer curve advocates will implicitly treat all growth as the consequence of tax cuts by indiscriminately crediting tax cuts as the cause of revenue growth. If after tax cuts the growth rate increased from 4.2 to 4.3%, tax cuts are at most responsible (assuming all else is unchanged) for the additional 0.1% increase, not the entire 4.3% growth rate and all revenues resulting from it.

The greatest economic role played by the 1920s tax cuts for the rich was likely in driving the stock market to unsustainable highs. You’ll notice that all of the Cato Institute figures on this topic always abruptly end in 1928.

The Kennedy-Johnson Cuts

The second major historical example comes from Kennedy’s 1964 tax cuts (which were signed by Lyndon Johnson after Kennedy’s assassination). This marked the first time that tax cuts were deployed explicitly as a strategy to boost economic growth. In some sense, Kennedy is the first supply-sider president. Kennedy’s tax cut lowered the top marginal tax rate from 91 to 70 percent; the lowest tax bracket from 20 to 14 percent; and the corporate tax rate from 52 to 48 percent. These tax cuts appear to have genuinely stimulated economic growth, which picked up rapidly over the next few years. Commenting on this, Laffer writes:

“In the four years following the tax cut, federal government income tax revenue increased by 8.6 percent annually and total government income tax revenue increased by 9.0 percent annually. Government income tax revenue not only increased in the years following the tax cut, it increased at a much faster rate.”

But those observations do not address the thesis of the Laffer curve. Government income tax revenue increases nearly every year because the economy grows nearly every year! —Using this same logic we could easily “prove” that raising taxes produces economic growth.— The relevant questions are whether tax receipts from those in the top tax bracket increased (They did.) and whether that increase was the consequence of economic growth stimulated by tax cuts (It was not). Economic studies suggest that the tax cut was not a primary driver of changes in economic growth or the growth of tax revenue.

Laffer also approvingly quotes Kennedy:

“In short, this tax program will increase our wealth far more than it increases our public debt. The actual burden of that debt--as measured in relation to our total output--will decline. To continue to increase our debt as a result of inadequate earnings is a sign of weakness. But to borrow prudently in order to invest in a tax revision that will greatly increase our earning power can be a source of strength.”

The US debt/GDP ratio did continue to decline for a while after Kennedy’s tax cut, but it had been declining since the 1940s. Ironically, the debt/GDP ratio would end up exploding under the king of supply siders: Ronald Reagan.

US Debt to GDP Ratio

Source: FRED

The Reagan Cuts

Reagan was the first president to act on Laffer’s then-novel theory, cutting the top marginal tax rate from 70 to 28 percent. This time, tax revenues did increase across the board, but this was expected. The economy was coming out of recession in the mid-1980s, so the tax base was growing regardless of whether taxes were cut. And to be clear, increases in tax revenues were more modest under Reagan’s presidency than they are during typical periods of economic growth. Even Laffer himself has a hard time making the case in retrospect. In 2004, he wrote:

“Prior to the tax cut, the economy was choking on high inflation, high Interest rates, and high unemployment. All three of these economic bellwethers dropped sharply after the tax cuts.”

This is a simple case of equating correlation with causation. Inflation was already coming down before the tax cut (and how would a tax cut reduce inflation?); unemployment began slowing in 1982, before most of the tax cuts came into effect; and even an ideologue as committed as Laffer cannot sincerely believe that it was Reagan’s tax cuts that compelled Paul Volcker to ease up on the federal funds rate.

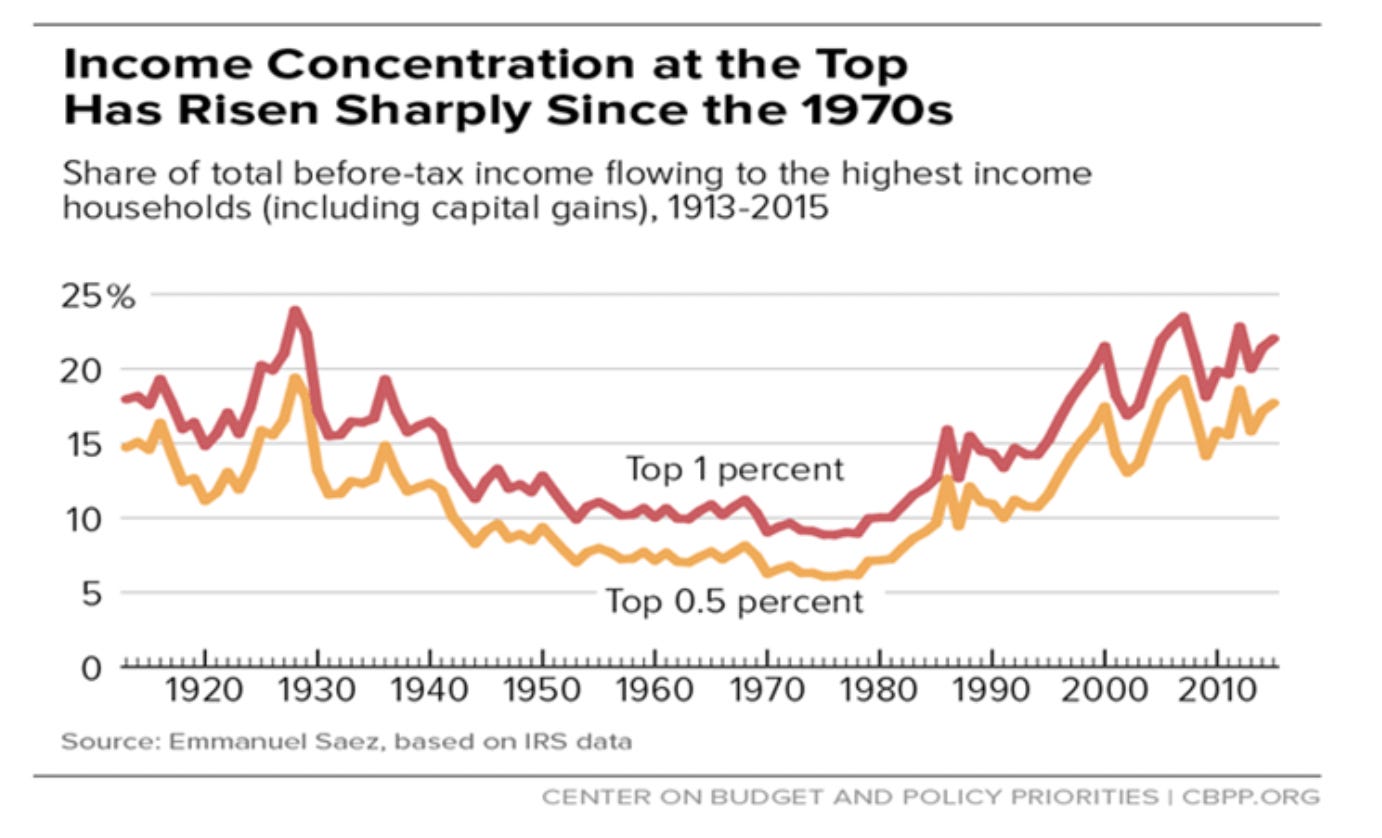

Another reason for the increased tax revenues under Reagan is the massive rise in income inequality during his administration. Because the rich are taxed at a higher rate than the poor, greater income inequality garners greater tax revenues for the government. Reagan, of course, promised that these benefits for the rich would trickle down to everyone else, but they did not.

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

The Trump Cuts

That brings us back to Trump. The last revision of the tax code was accomplished by his Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which permanently cut the corporate tax rate from 35 to 21 percent, and modestly reduced personal income taxes until 2025. Trump’s treasury secretary, Steve Mnuchin, announced that “the trillion and a half dollars of tax cuts we have made will pay for themselves.” They never did.

Following the TCJA’s passage, business investment slowed considerably (even turning negative in 2019). An IMF analysis found that only 20% of the money businesses received from the tax cuts went into capital investment and R&D; the rest went to dividends, stock buybacks, and other perks to shareholders that never trickled down.

Source: Center for American Progress

Tax receipts from corporations came in well below their pre-TCJA projected values, despite corporate profits being at record highs. Even the economic recovery (which had been ongoing since 2012 at that point) and the increasing inequality of the 2010s could not keep corporate tax receipts afloat after the tax cut. In the years after the bill passed (and before the COVID-19 pandemic), the federal budget deficit ballooned to nearly a trillion dollars. In response, Laffer has embraced denial, blaming government spending for the deficit and claiming that spending is a topic outside his purview.

Source: Brookings Institute

Source: Center for American Progress

In Conclusion

The economic arguments for the Laffer curve span nearly a century of history, but they always deploy the same few misleading talking points. First, instead of crediting tax cuts with the marginal economic growth they may cause, advocates of the curve implicitly credit all economic growth to tax cuts, assuming the economy (and thus the tax base) would remain forever stagnant without their cuts. Second, they ignore the role of income inequality in driving up the level and share of tax receipts paid by the rich; under a progressive tax system, greater income inequality will always result in greater tax revenues all else equal. Third, they rely on simple correlational analyses to reach their conclusions (The tactics outlined above do not survive econometric scrutiny). And lastly, they bury evidence that undermines their case, failing to take note of recessions and other macroeconomic factors that would bias their estimates. Notably, all of the major tax cuts discussed here were passed not long after the end of recessions.

The Laffer curve persists not because of its intellectual fortitude, but because of its political utility. It tells the wealthy that what’s good for them is what’s good for the world. And in a world dominated by the wealthy, those sorts of ideas are the hardest to shake loose.

Brilliant article! Wish I wrote it myself. Great points about how post-recession economic growth alone would have increased revenues anyway, and the effect of the progressive tax structure meant that only ultra-rich folks would be exhibit Laffer-esque behavior.

The only thing I would take issue with is the Reagan era. I do understand and mostly agree with your points, but it does seem like it was the right tax cut at the right time. Such a huge reduction of tax rate actually could produce more behavioral change across more people during such a high-tax, highly regulated eras. But the much lower reductions in the other era probably had a much more minimal effect.