The Great Society Didn’t Destroy Black America

Tim Scott’s revisionist history about the welfare state isn’t new, but it is wrong.

In our last post, we covered every economic claim made during the second Republican debate. Except one. An outlandish comment made by Senator Tim Scott was so broad and laden with historical baggage that I decided it needed its own post. Here it is:

“Black families survived slavery; we survived poll taxes and literacy tests; we survived discrimination being woven into the laws of our country; what was hard to survive was Johnson’s Great Society where they decided to put money, where they decided to take the black father out of the household to get a check in the mail. And you can now measure that in unemployment, in crime, in devastation."

The implication that the Great Society programs wrought more long-lasting destruction to Black families than slavery was roundly mocked by most of the media (though defended in The Wall Street Journal). The New Republic panned it as “embarrassing,” while The New York Times’ Nikole Hannah-Jones openly wondered how it must feel to need to “disgrace your ancestors to have a chance [in a Republican primary].”

But Scott is far from alone in his assertions. Famous Black economists like Walter Williams and Thomas Sowell have spent the last half century contending that government programs intended to help Black Americans have done more harm than good. (This blog will review Sowell’s recently-released book in the coming weeks.) Scott’s comments are an echo of Williams’ words a decade sooner:

“The welfare state has done to black Americans what slavery couldn't do….And that is to destroy the black family.”

So, how did it supposedly do so? First, we better talk about the history of the welfare state.

The federal government’s involvement in providing welfare benefits took off in the 1930s during the Great Depression. With millions of Americans out of work, waiting in bread lines for food while meager state unemployment funds dried up, mass mobilizations of Americans demanded action from the federal government, and FDR delivered. In the 1930s, Americans gained Social Security, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC, what is colloquially called welfare), a federal unemployment insurance system, a national labor relations bill, a vast array of public works projects resulting in the federal government directly employing over 8 million Americans, and the first bill setting national standards for wages and hours nationwide. After the Great Depression passed, Americans (increasingly even Black Americans) enjoyed broader prosperity alongside the nation’s growing welfare state.

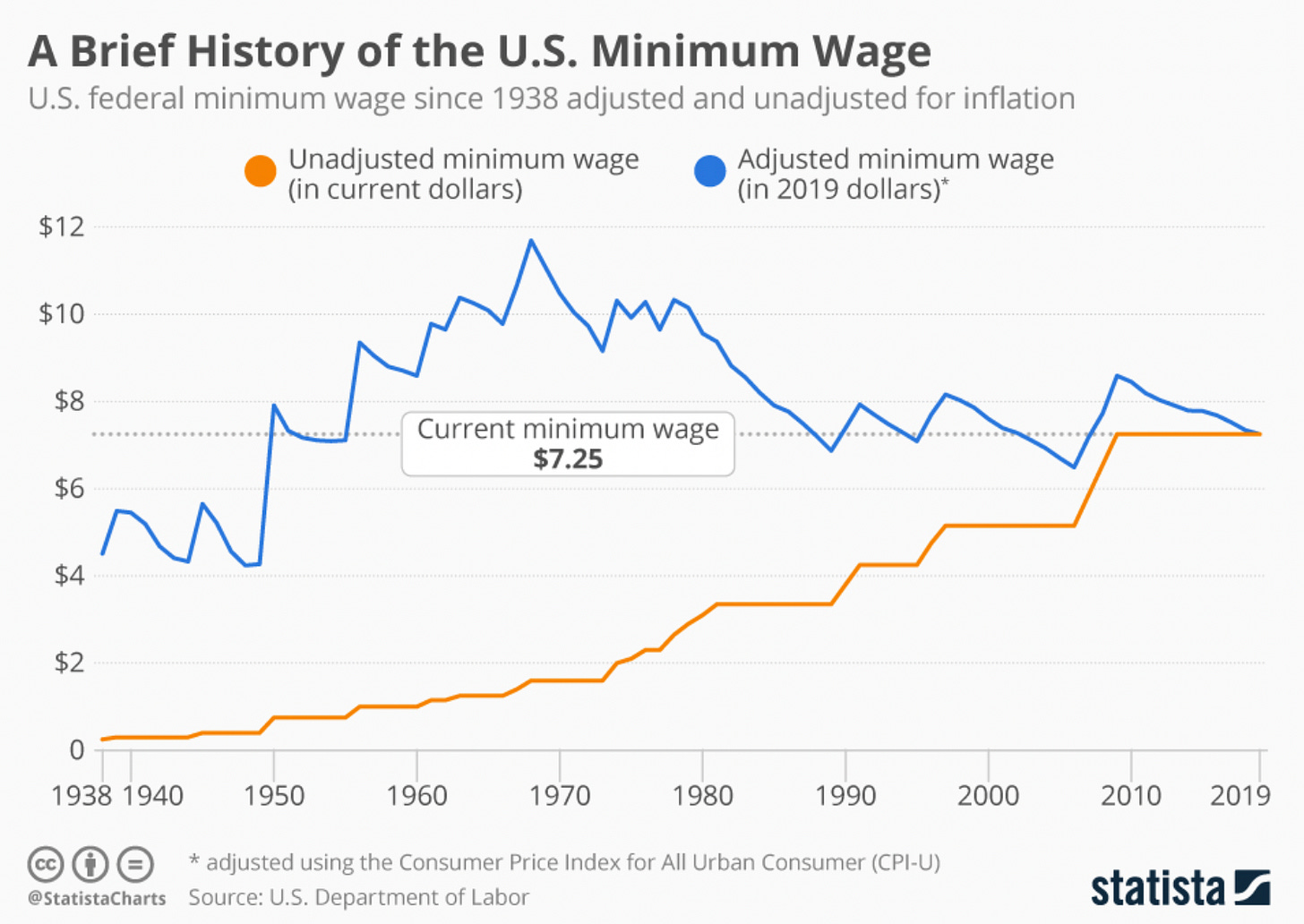

The second major expansion of the welfare state, more modest than the first, could not claim to be backed by a mass mobilization (except on civil rights) like the one that drove Roosevelt. While radical critics of the American economy, among them Martin Luther King Jr., were calling for new federal measures like a guaranteed universal income and a massive public jobs program, they were ignored. Still, Johnson passed many important reforms including the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid, the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, the expansion of food stamps, increased funds for poor school districts and Head Start for early childhood education, the Child Nutrition Act, and a reform to AFDC that would do more to incentivize work, all while overseeing one of the fastest real increases in the minimum wage. However, in the years after LBJ left office, America didn’t enjoy the same prosperity it did in its postwar years. High inflation, the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, deindustrialization, and the sexual revolution created a whole new country, for better and for worse, and many of the costs of this transformation were disproportionately borne by Black families.

According to its critics, the Great Society programs were largely responsible for driving Black Americans out of work, breaking up their families, and creating the sort of social or moral decay that resulted in the uprisings of the late 1960s and the longstanding issues of crime, unemployment, and single-parents homes in Black communities. However, as we’re about to see, the evidence for these propositions is slim and mixed at best. We’ll prioritize three topics here: wages, welfare, and the family.

Wages

The first labor laws to be subjected to the criticism of anti-Great-Society conservatives are actually FDR’s reforms in the aftermath of the Great Depression. Here’s a summary of that critique from Thomas Sowell:

“From the late nineteenth-century on through the middle of the twentieth century, the labor force participation rate of American blacks was slightly higher than that of American whites. In other words, blacks were just as employable at the wages they received as whites were at their very different wages. The minimum wage law changed that. Before federal minimum wage laws were instituted in the 1930s, the black unemployment rate was slightly lower than the white unemployment rate in 1930. But then followed the Davis-Bacon Act of 1931, the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933 and the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938 – all of which imposed government-mandated minimum wages, either on a particular sector or more broadly… By 1954, black unemployment rates were double those of whites and have continued to be at that level or higher.”

Sowell gets some things right here. Black and white unemployment rates were roughly equal in 1930, and they remained so in the 1940 census, despite all of the policies Sowell mentioned having taken effect. The Black unemployment rate would not become nearly double the white rate until the 1950 census.

Source: Vedder & Gallaway 1992.

But it’s more than a bit misleading to blame FDR’s labor laws for nationwide changes that appeared in the national data roughly ten years after their first implementation. Breaking down the census data Sowell uses by region provides much-needed clarity. The Black/white unemployment ratio was already nearly 2 to 1 in large parts of the North in 1930. Similarly, Black unemployment was lower than white unemployment nationwide because Black Americans disproportionately lived in the South where the unemployment rate was consistently lower than the rest of the country. The low wages, sharecropping system, and dependency of tenant farmers (not to mention the region’s relative lack of reliance on the financial sector) kept a great share of the population at work.

With this in mind, it’s unsurprising that as Black Americans continued to migrate to the North, the disparity between their unemployment rate and that of whites continued to grow. During the Great Depression in the early 1930s, Black Americans in the cities faced unemployment rates nearly double those of white workers. This came shortly before the first act Sowell mentions, the Davis-Bacon Act, took effect. It is true that the Davis-Bacon Act, which ordered federally-funded contractors to pay local prevailing wage rates wherever they worked pushed Black workers out of jobs, particularly in heavily-unionized industries where Black Americans were denied entry into the union. The NRA (which much of the Black press suggested stood for “Negroes Robbed Again”) had a similar effect, driving Black workers out of Northern industry.

Source: Vedder & Gallaway 1992

Even before these laws were passed however, Black workers in the North were often the “last hired, [and] first fired” during economic downturns. The available economic research suggests that the differences in the Black and white unemployment rates were primarily the result of Black migration to the North and into new industries, and, secondarily, increased racial discrimination on the part of employers who were at times aided by an unfortunate combination of pro-union legislation and whites-only unions. While I can find no attempt to measure the share of the unemployment differential caused by FDR’s labor laws, it is likely marginal. Less than twenty percent of Black Americans lived in the North in 1930 and, as seen above, the differential there was already near 2 to 1. By ignoring the chronology of the Great Depression legislation and the geographic variance of unemployment differences, Sowell has been able to present a simplified (and demonstrably wrong) narrative.

The second major contention put forth about minimum wage laws is that they disproportionately disadvantage Black teenagers, making it more difficult for them to find work. Here’s that argument from Milton Friedman:

“The minimum wage law is most properly described as a law saying that employers must discriminate against people who have low skills. That’s what the law says. The law says that here’s a man who has a skill that would justify a wage of $5 or $6 per hour (adjusted for today), but you may not employ him, it’s illegal, because if you employ him you must pay him $10 per hour. So what’s the result? To employ him at $10 per hour is to engage in charity. There’s nothing wrong with charity. But most employers are not in the position to engage in that kind of charity. Thus, the consequences of minimum wage laws have been almost wholly bad. We have increased unemployment and increased poverty…Moreover, the effects have been concentrated on the groups that the do-gooders would most like to help. The people who have been hurt most by the minimum wage laws are the blacks. I have often said that the most anti-black law on the books of this land is the minimum wage law.”

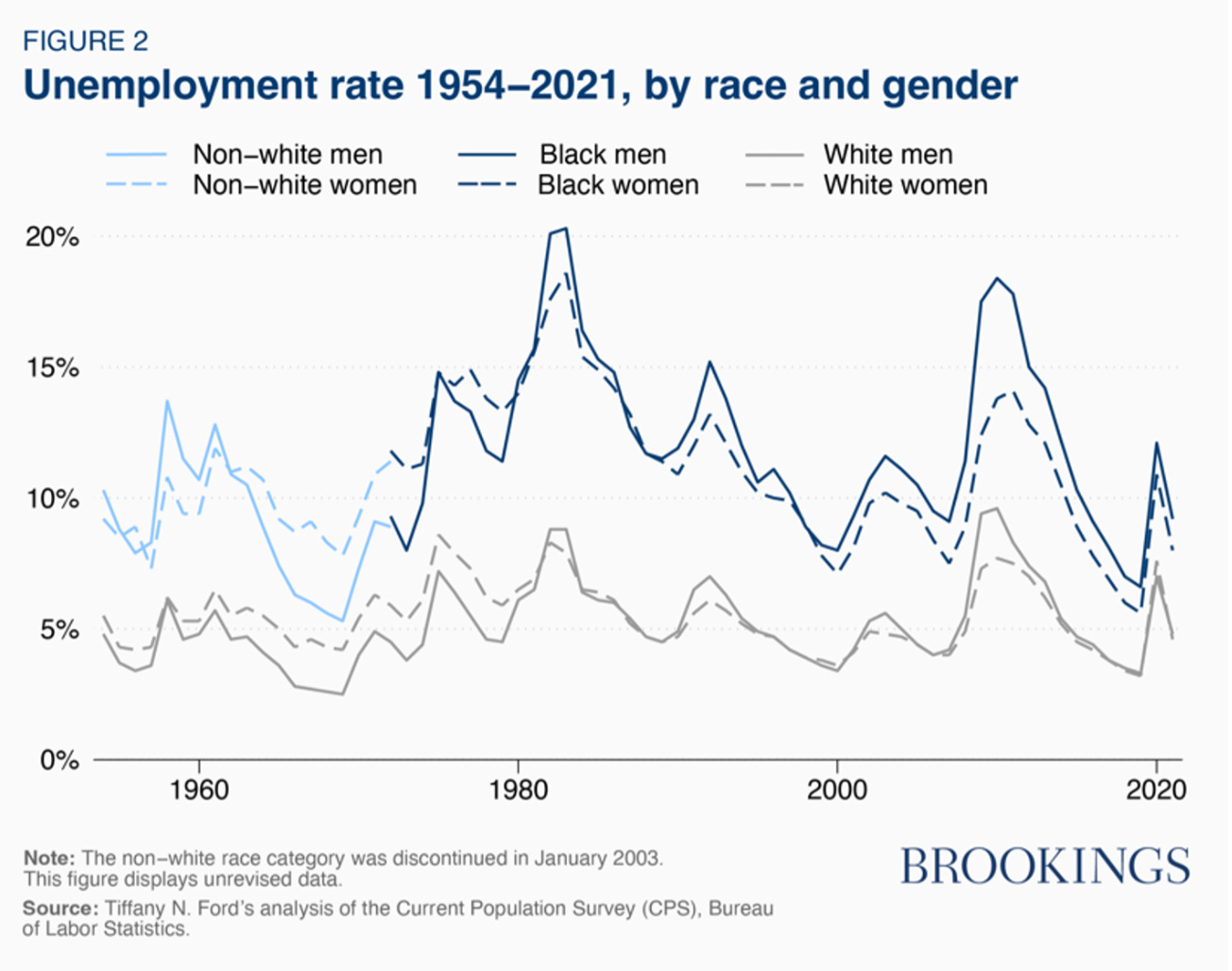

To argue that Black teens are the most disadvantaged by minimum wage laws (at least in line with the logic presented above) one would need to contend that they either have lower productivity on average than other teens or are more likely to suffer discrimination in the labor market as a result of their race. The economic literature on the effect of minimum wages laws is far too large to review here. But the general consensus is that minimum wage increases have a small to null effect on employment, but may have a small negative effect on Black teenage employment. However, it’s difficult to observe this effect in national unemployment data. (Go ahead, try.)

Source: FRED

There are two reasons for this difficulty. First, Black teenage unemployment was not tracked by the FRED database until 1972 (before then they used an outdated “nonwhite” category). Second, using the data at hand, the largest gap between Black and white unemployment (for Black adults generally and specifically for teens aged 18-19) took place not in the immediate aftermath of the Great Society, but in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a period where the real value of the minimum wage was falling and the welfare state was losing ground to inflation. If any trend is noteworthy, it’s that the “last hired, first fired” trend of the Great Depression appeared to still resonate in the 1980s, with Black workers experiencing much heavier cyclical unemployment than white workers during recessions.

Source: Statista

In these conservative discussions regarding the poor labor market prospects of Black teenagers, minimum wages are always something of a scapegoat. But once we leave the world of theoretical economics, it’s tough to pretend that white teenagers just make spectacularly better burger-flippers and retail cashiers than Black ones. Ignored are the consequences of white flight from the cities. As white residents moved to the suburbs during the mid-century, major cities lost their tax base and were forced to cut back on infrastructure and education, resulting in all sorts of social ills, less business investment and fewer jobs. Faced with the economic evidence (accompanied by a bit of common sense), a $7.25 federal minimum wage is probably one of the smallest stumbling blocks facing Black teenagers wanting a job.

Source: Brookings Institution

Welfare and the Family

The claim that expanded welfare programs under the Great Society somehow drove Black families to the brink has been repeated in several variations by conservatives. Here’s Thomas Sowell again:

“A vastly expanded welfare state in the 1960s destroyed the black family, which had survived centuries of slavery and generations of racial oppression. In 1960, before this expansion of the welfare state, 22 percent of black children were raised with only one parent. By 1985, 67 percent of black children were raised with either one parent or no parent.”

The statistics reported here are right, but again they lack context. The trend Sowell’s citing begins before the Great Society. In 1950, just 9 percent of black children were raised with one parent. That means that before Kennedy could even be sworn in, the portion of single-parent Black families had more than doubled. Determining why this happened is challenging, since a lot of the relevant data is only consistently tracked back to the mid-1950s. Additionally, there is no control population or easy counterfactual situation we can imagine to help us determine the cause in the rise of single-parent homes, though a lot of pop-sociology has attempted to do just that by invoking some vague decline in “family values” or the moral fiber of the Black community.

Without speculating too heavily, we will trace out a few relevant trends. First, the share of babies born out of wedlock by Black women rose considerably in the 1960s all the way to 2000 (It’s unclear if this trend began sooner). There’s no clear correlation between the generosity of America’s welfare state (which stagnated in the 1980s and receded in the 1990s) and out of wedlock births. To be fair, lots else was happening at this time, including the beginning of the sexual revolution and the widespread adoption of no-fault divorce laws.

Source: Institute for Family Studies

The amount of Black women who had experienced a divorce also continued to climb over the relevant period, though it had been climbing rapidly since the 1940s. Throughout this period, the Black divorce rate was significantly higher than whites, a fact that demands explanation from those seeking to blame the welfare state for racial disparities in social outcomes.

Source: Journeys at Dartmouth: Divorce Rates among Women by Race and Income

A more reasonable (though partial) explanation for these trends has to do with the changing economic conditions faced by Black Americans in the back half of the twentieth century. While the Great Society temporarily succeeded in bringing the Black poverty rate from 55 to 32 percent, the labor market opportunities for Black Americans continued to contract. The mechanization of cotton production in the South and the adoption of labor-saving technologies in the North (not to mention the competitive pressure added by expanding global trade) increased the number of redundant workers in the economy. And Black workers, disproportionately with less education and stuck in left-behind communities, were among the hardest hit.

These sorts of economic tribulations are brutal on family life. Low-income families, regardless of race, are significantly more likely to divorce, and disputes over family finances are a leading contributor to that. Low income communities are also the least likely to have access to birth control, family planning resources, and adequate sexual education while in school. All of these factors contributed to the twentieth-century rise in the unwed pregnancy rate among Black teen girls (and, in turn, absentee teen fathers). I’ll stop here, glad to have unraveled some trends, conceding that the picture discussed here is far too complex to fully unwind in this humble post.

We should now return to the claim that welfare tore apart Black families. The timing seems iffy at best, but even if we grant this theory the benefit of the doubt, through what channels did welfare accomplish this alleged feat? Proponents of this view are rarely so explicit, because beneath all of them lies an ugly assumption: Black families must be so money-grubbing or morally deviant that they would break up their marriages and abandon their children for a few extra hundred dollars a month (that the father, if he were the one to leave, would not even get). The assumption is both preposterous and racist, which is likely why even this theory’s Black supporters are rather shy about fully spelling out the logic behind their beliefs.

For instance, the main means-tested direct cash transfer program of the Great Society continued to be AFDC, but its average payout per recipient was only a few hundred dollars per month (It’s worth noting that nobody griped about the program’s socially ruinous impact when its recipients were primarily white in the 1940s and 1950s.) Much has also been made of the Supreme Court’s striking down of “man in the house” rules in 1968, which allowed single mothers who had male cohabitating partners to still receive aid if said partner was not the father or a caretaker for their children. The ruling has been alleged to incentivize divorce, and at the margins I suppose it might. The promise of an extra $200 a month might give a financially-dependent woman just enough financial stability to feel comfortable getting out of an unhappy relationship. But to think these effects could be anything more than marginal would be baseless and insulting. (Common sense helps here: When people discuss their divorces, they recall irreconcilable differences, affairs, and financial differences, not their lust for a little more sweet government cheddar.)

Source: Mother Jones

Conclusion

The narrative that the welfare state or Johnson’s Great Society decimated the Black family is in its most bold claims baseless, and in its more modest ones partial at best. It’s difficult to estimate the effects of many of these programs on Black America due to a lack of adequate historical data, the presence of several confounding social factors, and the lack of readily-available counterfactuals appropriate for comparison. To fill these gaps, some conservative intellectuals have woven articulate narratives that place blame squarely on the welfare state, but under scrutiny they fail to hold up. The trends they cite as damning frequently precede the programs they’re attempting to vilify. Their reliance on aggregate national data obscures structural economic realities that become apparent at the regional level. And their built-in assumptions about human nature (particularly of Black Americans) are so grotesque that we’d reject them immediately if they were ever applied to ourselves.

That said, some of the most vocal defenders of the views I’ve criticized above are Black, though they don’t hold such perverse assumptions about their own motivations. (Perhaps someone should ask Tim Scott if he would leave his totally real girlfriend for a few hundred bucks each month.) These figures are certainly not representative of Black opinion broadly, but their presentation as Black men willing to tell hard truths and buck liberal orthodoxy has bolstered their influence among conservatives, primarily for two reasons. First, it provides cover to less-well-intentioned whites who think that what Black parents really need is austerity and discipline meted out by tough conservatives like them. Second, the reverence these figures are granted for telling supposed hard truths about their communities (but again, not themselves) often overshadows the weakness of their arguments, which if exposed to a little sunshine would quickly wilt.

In response to the criticism he received for his debate comment, Scott released a Tweet:

“When Black conservatives speak up and speak truth, folks like you [Hannah Nikole-Jones, mentioned earlier] say to shut up & sit down. The only disgrace is those who seek to indoctrinate America’s children & lie about the greatest country on God’s green earth.”

Nobody’s told Scott to shut up. In fact, the reply to his outrageous claim has been a lot more muted than one would expect. But he has been mocked a bit, which is a reasonable consequence for making an outlandish claim and providing nothing in support of it.

This is going to touch a nerve but from my experience of nearly ten years as a teamsters steward at UPS warehouse there is a difference in entry level worker productivity that race is a powerful proxy for. It's essentially the macho "don't tell me what to do" attitude that is not caused by race but is powerfully correlated with it in young men, older workers tend not to have this attitude at all.

The amount of times I've had to intervene in an argument between workers and supervisors where the worker feels disrespected because the supervisor told them to get off their phone or to not walk in truck yard in which the worker was a young black man vs a young white man was absolutely observable. I even kept a private spreadsheet of firing for arguing or safety violations by race and age an. Both age and race were statically significant but young and black stood out head and shoulders above everything else.

Thomas Sewell also talked about this macho attitude and culture of not letting anyone disrespect you as to why rural whites and urban blacks look so similar.

I've always felt anyone who has talked politics or argued against the necessity have never known nor ever been in such a state where there was a need for welfare- but had "welfare" in the form of extended family money, or even state grants. Or even more cynically, DID get welfare, but felt in their case it was "deserved" and not for anyone else who was just "abusing it" unable to fathom that other people have hard times too.

Even my mom had a double take when we were talking about welfare and how she was against "welfare queens"...and then I just shut her up by asking if my sister, a single mom with two kids, could have been fine without food stamps? And got all quiet when I mentioned that she's imagining every worst stereotype guzzling up welfare, and not imagining every welfare recipient as her own daughter. Yes, my sister needed to find a better job to support herself and her kids...but when you have NOTHING, you can't get anything- and you're less capable of getting something- can't work if you can't eat, and being homeless costs more monthly than having a home. The hope of welfare is that with an easier first step, you can move upwards to a better paying job.

For everyone else- the injured, the elderly, the disabled, they still often work- they still engage with their communities- and even as per capitalism, they consume and put that money immediately back into the economy. Unlike rich people, who hoard and tax haven, all of that welfare money goes into a local community, it is returned to the US when taxed. Obviously, the real issue is that much of that welfare money is then hoovered up by the likes of Walmart who then go out of their way to deny Uncle Sam his tax dollars.

The denial of welfare assumes that just as all Americans are "temporarily embarrassed millionaires", the opposite can never be true: no one who "works hard" will ever fall down and be unable to live on their own means- no one can ever become a millionaire temporarily embarrassed. For the super rich- this is true, they have enough wealth and connections that pay like wealth to recover. Sometimes even the idea that they could be worth something again eventually is enough scrip to get someone to feed and clothe them. But for the average American, especially as most of us can barely hold up $300 in savings to deal with emergencies and are constantly being knocked down by medical emergencies, and the greatest amount of equity we keep is our cars (a depreciating value at that), we have to accept that one day, we will fall short, and there may be no one to help us, no matter how hard we work.

Family pockets and GoFund me are like an elective welfare- but an unnecessary one, and one fraught with abuse and misuse. Yes, someone could fake an injury and get a whopping $500 monthly so they don't have to work...but someone could also just choose not to work and do drugs and leech thousands of dollars a month from family members or outright defraud Gofundme-like ventures, as there's no limit nor any control on how they use the money they ask for.

For me, my biggest gripe is that the people who yell the loudest are those who imagine their precious and hated tax dollars (ones they, if they could, would not pay any at all) going towards someone they detest, despise, and are disgusted by, imagining the 1 or even 0.01 cent of their tax money going into one venue, and ignoring the more obvious boons of their tax dollars in the roads and bridges they drive upon, the public services they frequently take advantage of, and the numerous subsidies their businesses rely on to turn a profit.

Sowell and his ilk like similar Libertarian/Sov Citizen Rashad Jamal, are in a weird category of public speakers in that community who would actively try and create a following of thought that would actually make the average member of the black community's life harder, more painful, and less capable of dealing with the issues we face today, while framing it as "empowerment" or "taking control" away from a nebulous, evil government...while they themselves are immune (not so in the Rashad example fortunately) are immune to these hardships due to their own privilege, peerage, and high paid career. Men who live in an oasis telling people who live in the desert that they don't need to live under the tyranny of "water".