Australian real estate CEO Tim Gurner made headlines this week for some callous remarks about workers. Speaking at the Financial Review Property Summit, he said:

“I think the problem that we've had is that we’ve… people have decided that they didn’t really want to work so much anymore through Covid, and that has had a massive issue on productivity. Tradies [laborers] have definitely pulled back on productivity. They have been paid a lot to do not too much in the last few years. And we need to see that change. We need to see unemployment rise. Unemployment has to jump forty, fifty percent in my view. We need to see pain in the economy. We need to remind people that they work for the employer, not the other way around.”

After widespread condemnation, Gurner backed down and issued an apology for these comments. But, as Jacobin has pointed out, Gurner’s comments are not far from what the economists at the Federal Reserve have been trying to orchestrate. Despite declining demand being responsible for only a small fraction of the reduction in inflation over the last several months, the Federal Reserve has consistently pushed the federal funds rate upward. Ostensibly, this is to bring inflationary expectations back down to normal and avoid a return to high inflation, but it also conveniently helps restore the class power of America’s businessmen after they found themselves having to more vigorously compete to hire workers after the pandemic. The goal, stated explicitly by insiders like Larry Summers, is to force the unemployment rate up, making workers more desperate for jobs and willing to settle for lower wages.

In these sorts of discussions, you may often notice a certain tension. Workers apparently have it so good, but also suddenly nobody wants to work. Could both be true? In economics, this tension is expressed through the substitution and income effects. The substitution effect describes the desire to work more after a wage increase so that one can spend more hours getting paid at a higher wage rate; the income effect describes the desire to work less because one could earn their desired monthly income in fewer hours. However, these two effects are consistently found to cancel one another out. Most workers don’t realistically have the option to work a few hours less per week, nor can they suddenly get overtime once they get a raise.

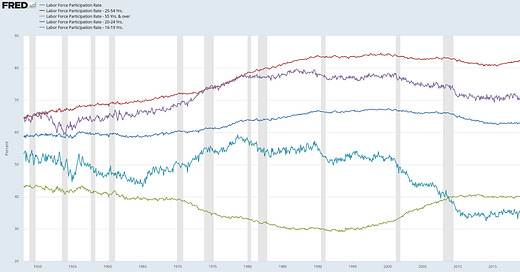

Critics of the current labor market have attempted to resolve this dilemma by contending that millions of Americans are still living fat and happy on pandemic-era stimulus (which ceased more than two years ago), but it appears that labor supply in the post-pandemic economy has largely reverted back to normal. The labor force participation rate (i.e. the percent of people that are employed or actively seeking work) has returned to pre-pandemic levels for all age groups except those aged 55 and older. Their labor force participation has barely recovered since March 2020. The unemployment rate has also been below 4 percent for the last eighteen months.

Labor Force Participation Rate by Age Group

Source: FRED

With these numbers in mind, why does the (historically persistent) myth that “nobody wants to work” refuse to go away? There are many reasons, but here are the big two.

First, political analyses of this issue (and often public opinion) seem to be heavily influenced by data that is at least twenty-four months out of date. In 2021, it would have been accurate to note that labor force participation had not recovered; today it is not.

Second, labor markets have become tighter since 2020. The unemployment rate is near record lows; labor force participation is at its highest rates since the early 2000s; there are more job openings than workers; and workers are increasingly mobile between industries thanks to the shake up (and free-time available for reskilling) that was granted by the pandemic. All of these factors have helped drive up wages. Nominal wages have climbed quickly, and even real wages have consistently increased over the last several months. It’s not that nobody wants to work. It’s just that nobody wants to work for the lousy wages that bosses could previously get away with.

Not only have workers achieved higher wages, in many instances they have won greater autonomy both inside and outside the workplace. This has come in the form of greater benefits, more vacation time, and more opportunities for remote work. It turns out that with no slack in the labor market (or, if you prefer Marx’s term, no “reserve army of labor”), your boss might be forced to suffer the indignity of treating you a bit more nicely. And, despite Gurner’s complaints, these perks have not resulted in a decline in worker productivity, which has grown roughly in line with pre-pandemic trends.

Nonfarm Labor Productivity for All Workers (2018-Present)

Source: FRED

Additionally, despite the gains of workers, even corporate profits remain at highly elevated levels.

Corporate Profits After Tax

Source: FRED

This is the proper context for Gurner’s remarks. Bosses are still doing remarkably well, but workers have managed to negotiate a slightly better deal for themselves. Even these marginal gains feel like too great a slight to some businessmen. In the coming months, you’ll hear many more complaints just like Gurner’s. Just yesterday, as the United Auto Workers (UAW) announced they were going on strike, CNBC’s Jim Cramer called for their jobs to be shipped to Mexico, a position only slightly less absurd than his comparison of UAW President Shawn Fain to former Communist Party USA Chairman Earl Browder.

Instead of adapting to the new labor market conditions, businessmen and their media allies will continue to cry foul and call for the government to come save them by raising the federal funds rate, inhibiting union activity, and passing other pro-employer measures. So far, the Biden administration has largely sided with workers (despite a few temporary lapses), while the Federal Reserve plays bad cop and continues to try and cool the labor market with tight monetary policy.

In a recent Gallup poll, 75% of Americans reported sympathizing with the UAW over the automobile companies. Perhaps it’s not the workers, but the bosses who should be made to endure a little more pain.

I suspect Tim, who's also the avocado toast guy, just does this stuff for pure marketing purposes. After all, he's not insulting those who fund and purchase his high end luxury apartments he pushes out people to build.