What The Hell is a Reverse Market Crash?

How Patrick Bet-David uses anti-elite rhetoric to push pro-elite policy (and scare the pants off people)

As inflation continues to cool, economic analysts have become optimistic that the Federal Reserve will soon stop raising —and perhaps may cut— interest rates. As a result, S&P 500 futures have been rising steadily as investors gain confidence in the future of the economy.

This sounds like good news. The Fed has seemingly accomplished its goal of a soft landing, even if it didn’t come quite as the institution predicted. Now, the cost of borrowing can be eased, businesses can invest more at lower cost, and we can watch unemployment remain low and real wages tick upward.

However, a brigade of constantly doomsaying pundits are rushing to publish videos and articles about how we should not prematurely celebrate and how rate cuts could actually harm the economy. Perhaps the most absurd reaction comes from the entrepreneur and podcaster Patrick Bet-David, who is now warning about the possibility of a “reverse market crash.”

I know what you’re thinking: wouldn’t a reverse market crash just be a market boom? Yes, it seems so. Bet-David explains:

While traditional market crashes are characterized by rapid declines in asset values, a reverse market crash involves an excessively rapid rise in market values, leading to potentially dangerous economic consequences… [This is] something [the] wealthy would want, but not something you’d want for low and middle America.

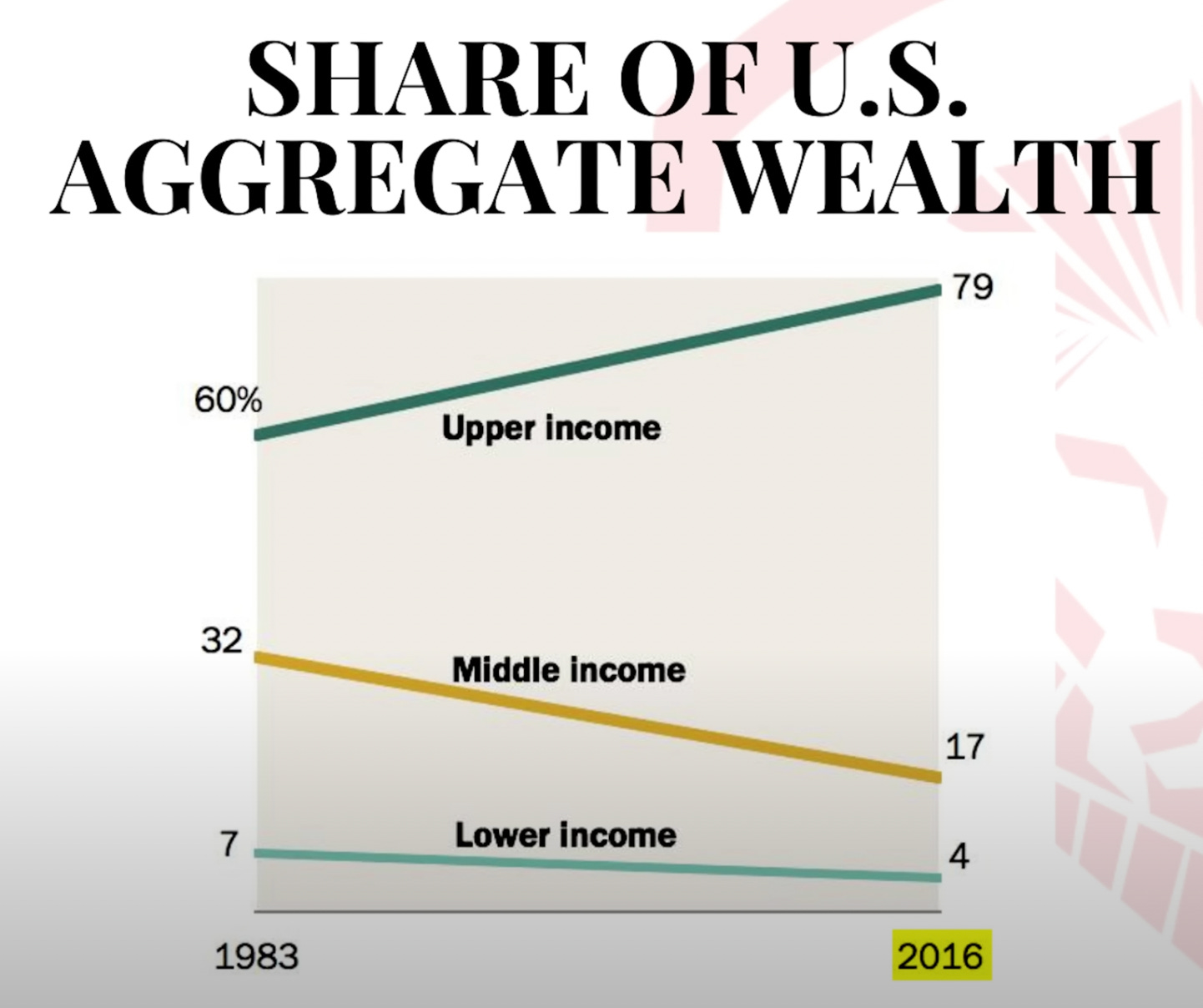

To be fair, there’s an ounce of truth to this. The Wall Street Journal reporter Nick Timiraos has done a great job documenting how persistent low interest rates can fuel asset bubbles, malinvestment, and wealth inequality. The latter point is highlighted by Bet-David, who points out the growing gap between the rich and middle class in America.

This shouldn’t be surprising. The top 10% of Americans in terms of wealth own 89% of all US stocks. Of course these people are going to benefit the most from rising asset prices. However, there are other benefits of lowering interest rates; it can lead to faster job creation and higher wages, developments that disproportionately help the poor and middle class. Furthermore, as Bet-David’s graph suggests, rising wealth inequality is a secular problem; despite booms and busts, wealth inequality has tended to increase, though that accumulation can be temporarily hindered by real (not reverse) market crashes that reduce the value of the assets owned by wealthy individuals more quickly than the value of assets owned (or owed) by poorer ones. But that’s not an appealing situation either; we all become more equal through our collective impoverishment. Since the late 1990s, the rich have seen their wealth increase much faster than the poor and since the Great Recession, only the top quintile of households have seen their net household wealth increase.

After signaling that a reverse market crash would be bad news for the poor, Bet-David gives us some historical examples of these sorts of crashes from around the world. Given the definition provided to us earlier, you would think that Bet-David is about to discuss instances where rising market values produce some sort of malinvestment or untenable inequality. Instead, Bet-David turns the discussion to inflation. Inflation will produce rising nominal valuations, but it tends to have a negative impact on real asset values, which is certainly the case in the examples given by Bet-David. He discusses Weimar Germany, Zimbabwe, Turkey, Argentina, Venezuela, and Iran. His explanations are pretty straightforward and bear the usual limitations of taking only a single minute to try and unravel the economic complications of each of these countries. In short, Bet-David blames excessive money printing for these crises. While that’s an overly-simplistic explanation it’s not totally wrong, though it is unclear how these alleged “reverse market crashes” are something the “wealthy would want.” The elites of Weimar-era Germany did not fare particularly well after hyperinflation.

These examples might feel disconnected from American economic circumstances. Zimbabwe faced 24,000% inflation, while Germany reached 29,500%; both nations printed soon-to-be useless trillion-dollar banknotes. Is that really comparable to the American situation, where inflation briefly touched 9%?

Bet-David anticipates this critique:

Now, you may be saying, Pat, all these examples you’ve given. We’re not Zimbabwe. We’re not Turkey. We’re not Iran. We’re not Venez[uela]… Are you out of your mind? That’ll never happen to us in the US. Okay, let me show you a couple things here… Maybe you’re right, maybe I’m wrong. Who knows.

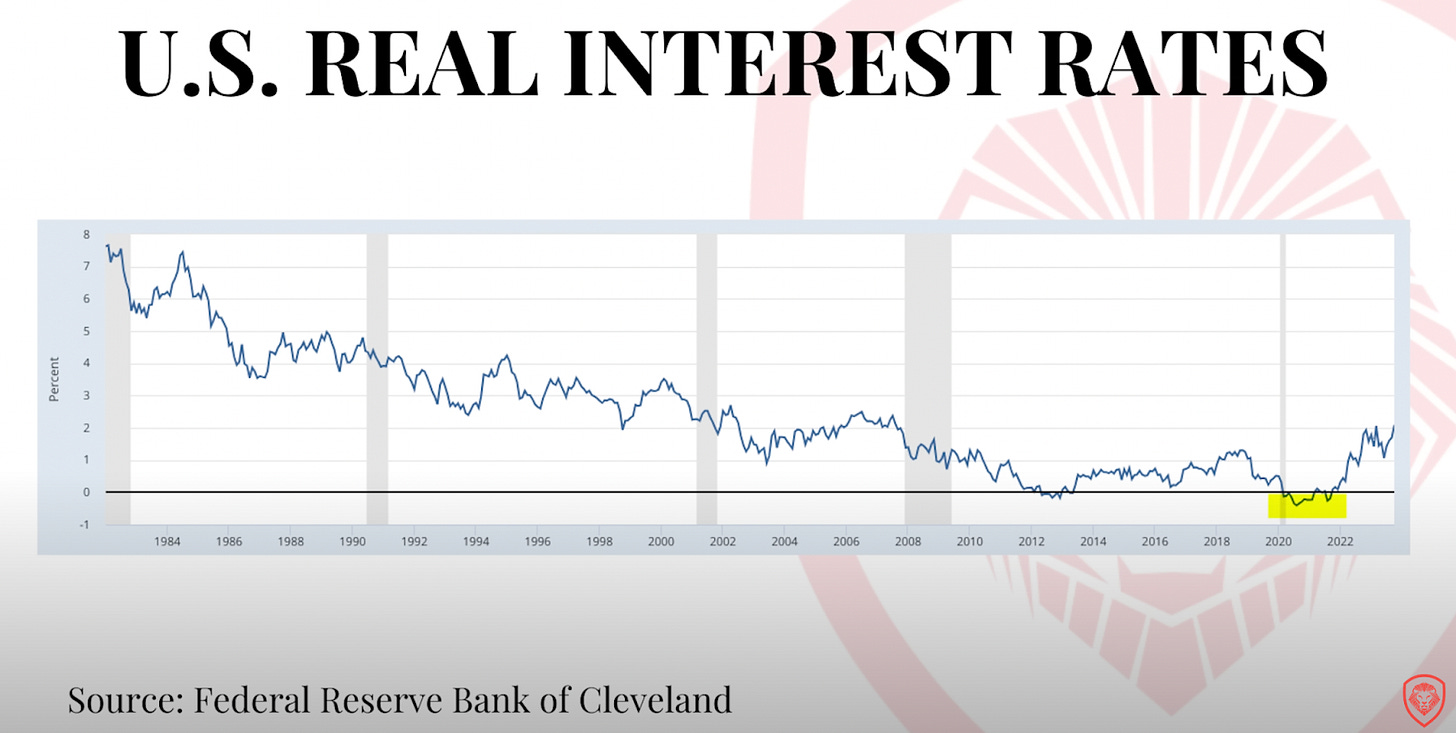

Bet-David proceeds to show the following graphs on screen, noting that inflation was briefly higher than usual after the pandemic, that real interest rates have temporarily gone below zero, and that the effective federal funds rate has spent several months at 0 (though isn’t there anymore). It’s not clear how these prove his point.

He also cites the fact that the S&P 500 has grown by a factor of six since its low-point during the Great Recession. That may be an indicator that stocks are overvalued—which could be the result of excessively low interest rates, government spending, irrational investor exuberance, or all three!— but it’s not evidence of oncoming Weimar-style inflation. Similar wrong predictions were made by many commentators following the Great Recession. They wrongly argued that the cycles of quantitative easing pursued by the Fed would result in hyperinflation. Bet-David persists in blaming quantitative easing for inflation, but he tends to define it less precisely as “money printing” or any instance where borrowers are able to accumulate greater debts. These redefinitions only serve to make him more wrong. Despite all of our quantitative easing, inflation has rarely been a significant issue over the last thirty years.

If these graphs failed to convince you of oncoming catastrophe, Bet-David restates his thesis a bit more concretely:

In America, if Powell all of a sudden gets pressure from the top to say lower interest rates, inflation could go back up again quickly… If he lets loose, you’re talking about [a] reverse market crash we will experience in the US.

Some mainstream commentators have also fretted that Powell’s decision to stop raising interest rates could cause inflation. Even if those commentators are correct (I don’t think they are), I’m not sure if a return to 7% inflation constitutes a reverse market crash. It certainly comes nowhere near the magnitude of the examples Bet-David provided.

Bet-David then goes on an unorganized rant, blaming the potential for a reverse market crash on “when the government chooses to get involved in free markets,” “price controls,” “more welfare spending,” “more money printing,” “this idea of reparations,” “UBI,” “the World Economic Forum”, and “[the potential adoption of a universal] digital currency.”

Bet-David seems to be suggesting these as possible threats, rather than the cause of some oncoming reverse market crash, but it’s unclear. He must know that pandemic-era welfare expansions have been rolled back, that price controls haven’t been tried in post-pandemic America, that the deficit has been shrinking, and that reparations and UBI are nowhere near a reality. This marks the emotional crescendo of Bet-David’s video. Gone are the didactic lectures about rising wealth inequality; he’s now transitioned into a full-blown paranoid conservative.

Bet-David’s commentary is a maze of redefinitions and obfuscation. Despite his original, somewhat creative definition of a reverse market crash, it appears he’s just referring to hyperinflation. Nearly three-quarters of his video is devoted to facile explanations of what has happened in countries that faced hyperinflation. If you think it’s ridiculous to suggest that we’re facing such dire straits, Bet-David first bombards you with graphs that don’t make his case and then embraces the paranoid grandma tactic of quickly listing off every imaginable conservative economic bugbear, from the traditional to the conspiratorial.

And what’s Bet-David’s solution for the oncoming catastrophe? Surely he’d advise the government to not get involved in free markets, implement price controls, or pay reparations to the descendants of slaves. Prescriptively, he’s called for quantitative tightening in other videos. But in this video, he only gives one proposal: buy art.

Billionaires and millionaires understand that one of the ways to hedge against inflation… is to buy non-duplicatable assets and one of them is art.

But this is actually just an ad for a pretty shady company called Masterworks which lets investors buy fractional shares of art. Lots of rich people do invest in art —it happens to be great for money laundering and tax avoidance— but I’ve never heard of any of them wanting to buy illiquid, intangible, fractional shares of art. But maybe I just don’t know enough rich people.

So what is a reverse market crash? Well, it’s either hyperinflation, a return to pandemic-era inflation, or an unsustainable rise in (nominal?) asset values. Bet-David conflates all of these things into one. He may not succeed in providing a clear explanation of what a reverse market crash is or why it's supposedly “worse than a [regular] market crash,” but if his comments section is any guide, he has succeeded in terrifying his audience.

Catching up on your posts this morning. Definitely enjoy your explanations, although I took slight offense at your term of paranoid grandma. I’m a first-time granny at 78 who is trying to understand the financial universe better than I have before. Thank you for your clarity.

I'm pretty sure that gold and oil are going to outperform art when everyone takes a step down the pyramid of mazelow's hierarchy of needs.