Writing well is a skill that few people possess and that fewer people are encouraged to develop. Before entering economics, I briefly considered a career in journalism. Mentors advised me to buy a copy of Strunk and White’s classic The Elements of Style,1 a book designed to cure novice writers of bad habits. No superfluous words, run-on sentences, or grammatical errors should be left to distract the reader’s attention, it advised. When my interests shifted to economics, I bought a similar guidebook: Deirdre McCloskey’s Economical Writing.2 I have always considered good writing to be an intellectual and aesthetic craft, a product that both conveys information and is a pleasing read.

I know this view is widely considered antiquated. Writing —if valued at all— is valued only for its ability to convey ideas. Philistinism abounds and for many economists the words they write are the least important aspect of their research. The written word is merely padding that insulates the much more essential figures, tables, and equations. This tendency has gotten so extreme that I know of several colleagues who outsource vast portions of their writing process to artificial intelligence. The result is a rigid text, as precise in its phrasing as it is devoid of individual style.3

Perhaps these criticisms could be dismissed as those of an aesthete or a Luddite— someone rejecting how a revolutionary technology is diminishing the value of his skills and upsetting his conception of beauty. Maybe champions of old-fashioned writing will one day look as silly as opponents of the power loom or genetically modified agriculture. But I doubt it because writing on one’s own also has great pedagogical utility. One can ponder an idea or mindlessly run regressions for hours, but beginning to type imposes discipline. One gets stumped putting pen to paper not merely because they are a “bad writer” but often because they don’t have a sufficient grasp of what they are doing. They lack historical or contextual background; they don’t have the evidence they thought they had marshaled; or they failed to consider possible rebuttals until attempting to write rendered clear the objections one could raise. In short, freedom from the burden of writing risks producing a certain intellectual sloppiness.

The same is true regarding the poor reading habits of today’s young economists. When reading papers they skim only the abstract and key figures. Of course, there’s nothing outrageous about this considering that is where all of the author’s attention likely was anyway.4 Much more concerning is that young economists today rarely read books. At most, they may have read one of the popular behavioral economics tracts, a recently published policy book, or perhaps some heterodox literature—which must have limited returns when one is so unfamiliar with orthodox views.

This illiteracy is often on display in a microeconomic theory class that I am currently taking. The professor is of an older generation—with a deep respect for economic history and the theorists that came before. Time and again, he will ask the class to raise their hands if they have any familiarity with the works of a commonly known figure. Joseph Schumpeter, Milton Friedman, Karl Marx, and John Rawls have all been mentioned. Without fail, less than six of the thirty people in the room will hesitantly raise their hands, some assuredly hopeful they won’t have to field a follow-up question. Of course, it’s perfectly forgivable to have never bothered wading through Capital or A Theory of Justice,5 though having so little knowledge of these men’s contributions is less excusable and suggests a stunning unfamiliarity with even the secondary literature surrounding their work.

I suppose one could hypothetically be very knowledgeable about Milton Friedman’s work without knowing the man’s name. Maybe we can have economic brilliance alongside historical ignorance! But again, I doubt it. One could be familiar with monetarism and the quantity of money equation (the famous PY=MV) and understand it mathematically but its true significance can hardly be appreciated without an understanding of twentieth-century Keynesianism, the Volcker Fed, or the volatility of all its variables.6 Perhaps one could slowly piece together an adequate picture without opening a book by trodding through old issues of several different economic journals, but this is the equivalent of mowing your lawn with a weed-whacker because you refuse to learn how to operate the push mower.

The aversion to books in particular frequently comes from a lack of familiarity with them. Reading is not an easy habit to build. The physical and mental difficulty of it was well put by Antonio Gramsci— who must have understood it better than most given the chronic pain he endured:

In education one is dealing with children in whom one has to inculcate certain habits of diligence, precision, poise (even physical poise), ability to concentrate on specific subjects, which cannot be acquired without the mechanical repetition of disciplined and methodical acts. Would a scholar at the age of forty be able to sit for sixteen hours on end at his work-table if he had not, as a child, compulsorily, through mechanical coercion, acquired the appropriate psycho-physical habits? If one wishes to produce great scholars, one still has to start at this point and apply pressure throughout the educational system in order to succeed in creating those thousands or hundreds or even only dozens of scholars of the highest quality which are necessary to every civilisation.7

I am far from the first to have leveled these critiques at the economics profession. A whole crop of political economy programs have been founded in recent years attempting to address some of these shortcomings. But oftentimes, in the name of challenging ideologically dominant neoliberalism and promoting interdisciplinary collaboration, the courses offered in these programs are light on economics and heavy on other disciplines. A glance at the syllabi listed on the website from Yale’s popular Law and Political Economy Program yields courses in “Law after Neoliberalism”, “Law Social Movements, and Social Change”, and “Law and Inequality.”8 None of these syllabi contain any applied economics papers, though they do contain several essays written by great economists and other researchers. Lest you think Yale’s program is an outlier because of its dual focus on law, consider that the political economy degree offered by Williams College —held by both Lina Khan and Oren Cass— does not even require its students take calculus.9 This extreme neglect of mathematics —and much of economics— is bound to produce faulty reasoning. For instance, Oren Cass was recently widely mocked on X (formerly Twitter) for an elementary misunderstanding of Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage. But what is even more concerning is that he frequently writes as if Ricardo had the last word on international trade, and that the problem with economics is that it hasn’t moved forward since (Heckscher-Ohlin, anyone?)10 Though perhaps this shouldn’t be too surprising. Without calculus or higher mathematics, it’s impossible to discuss economics as it was developed through the twentieth century. How can someone discuss marginalism, Lagrange multipliers, or the contributions of Gerard Debreu or Tjalling Koopmans when they stopped reading at Adam Smith and pre-calc?11

This is not to say that studying political economy is done in vain. After all, so much of the governance and regulation of our economic system is political, and economists have historically been slow to appreciate that. The many successes of Lina Khan —in slowing corporate concentration, promoting competition, and eliminating non-compete agreements— are a testament to the relevance of political economy. But this kind of intellectual cross-pollination is exceedingly rare. The overwhelming tendency is toward an academic division of labor in which mainstream economists remain illiterate but mathematically brilliant, while political economy folks become more literate but remain economically challenged.

There is room for optimism here. I have heard a great deal of frustration from economics PhD students who are aware of their illiteracy. They are hungry to know more about the history of their field and its connections to other disciplines, even if the academic job market does not necessarily incentivize that curiosity. In a field where just a few hundred are brought into the top programs each year and where a small number of researchers can have a disproportionate impact, there is genuine hope that young economists who embrace literacy —and maintain mathematical rigor— could change the course of our profession for the better.

White, Elwyn Brooks, and William Strunk. The elements of style. Open Road Media, 2023.

McCloskey, Deirdre Nansen. Economical writing: Thirty-five rules for clear and persuasive prose. University of Chicago Press, 2019. One of this blog’s earliest posts was a review of McCloskey’s Leave me alone and I’ll make you rich:

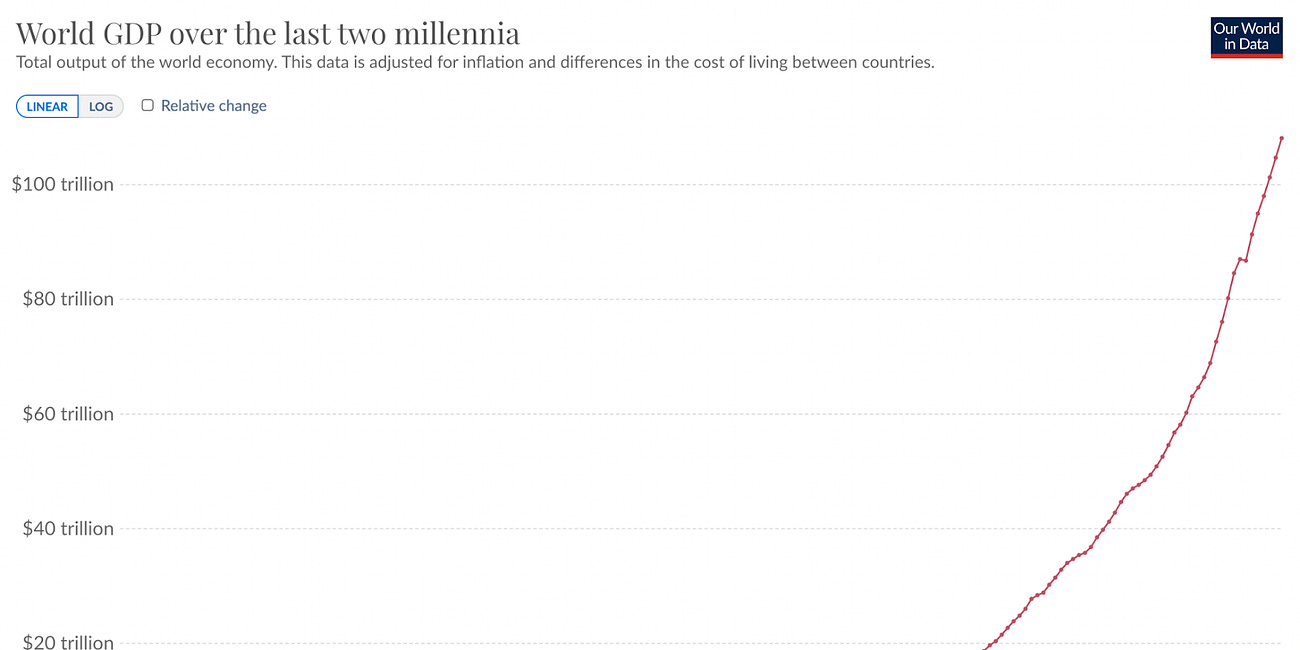

The Libertarian Telling of Economic History is Unserious

Leave Me Alone and I’ll Make You Rich is the latest work of Deirdre McCloskey, a prominent economic historian and libertarian, and her co-author Art Carden. Both identify themselves as classical liberals and their book makes the case that the spread of certain “bourgeois values” is responsible for the massive surge in economic growth the world has exper…

The quality of AI-written text can be quite good. Several studies have found humans unable to detect the difference between human and AI-generated content, and some AI companies brag that their model has been trained to write “like Shakespeare.” Regardless, economists do not bother chastising ChatGPT, Claude, or DeepSeek for more elegant prose.

However, I do think something is lost in our neglect of literature reviews.

That said, more economists should read these books.

A recent book handles these topics well. Burns, Jennifer. Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023.

Hoare, Quintin, and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. Selections from prison notebooks. Lawrence & Wishart, 2005, pg 37.

See: https://lpeproject.org/syllabi/

See: https://political-economy.williams.edu/the-major/major-requirements/

Cass, Oren. “Free Trade’s Origin Myth.” Law & Liberty. January 2, 2024. Probably a lot of people could benefit from reading of Helpman, Elhanan. Understanding global trade. Harvard University Press, 2011.

For a good discussion of mathematics in economics, read the book below. Of particular interest is the chapter “Sidney and Hal” in which Weintraub details the challenges faced by his father, an aspiring economic theorist with woefully inadequate mathematical preparation. Weintraub, E. Roy. How economics became a mathematical science. Duke University Press, 2002.

Found this to be a timely reflection. As someone studying economics, I’ve felt the tension between technical rigor and intellectual depth — especially when writing becomes a mere vessel for models, not an exploration of meaning. The loss of narrative, historical context, and even curiosity in how we present and engage with economics isn’t just stylistic — it weakens the discipline.

I see writing to be a process that forces, and even requires, clarity. It is the perfect proxy for thinkings. I share your optimism — if more young economists embrace literacy and mathematical fluency, the field has room to evolve meaningfully.

Illiterates turning a dismal science into a banal solipsism? Reading is an art; not reading is anarchic, of the character of banality. Do the illiterates actually have any utility, marginal or otherwise, as economists? https://aworldeofwordes.substack.com/p/reading-is-an-art?r=5d7dmx