The Inflation Reduction Act Lives Up To Its Name. Well… Maybe

New research suggests that inflation was primarily brought down by an expansion of supply: a possible victory for Bidenomics.

When the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was first passed, its name was subject to a lot of mockery. Republicans were incredulous at the idea that a bill creating $485 billion of new spending and tax breaks would bring down inflation, and many Democrats were quietly in agreement. The bill was trumpeted as anti-inflationary for three reasons: 1. It would reduce the federal budget deficit by $300 billion over the next ten years 2. It would allow Medicare to negotiate prescription drug prices, reducing healthcare costs and 3. It would make investments in clean energy, thus driving down energy bills. But most economists were skeptical that any of these would significantly reduce inflation. A Moody’s estimate, cited even by one of Biden’s top advisers, estimated that the IRA would only reduce the consumer price index by a third of a percentage point over the next decade. Even the White House seemed skeptical. Their fact sheet on the IRA never once directly mentions reducing inflation as an achievement of the bill. Just weeks ago at a fundraiser Biden lamented the name, saying “I wish I hadn’t called it that.”

However, to the surprise of many, inflation has come down rapidly since the passage of the IRA in August 2022.

Source: FRED

Not only that, since the passage of the IRA, inflation in the United States has gone from being among the highest in the world’s developed countries to among the lowest. Some of this is just a function of superb timing. The IRA’s passage happened to coincide with declining energy prices, but that’s only part of the story. These trends persist even if one looks only at core inflation (a metric that excludes food and energy prices, which tend to be volatile).

Source: CEA

These results run contrary to the predictions of many economists who have spent the last two years arguing that for inflation to cease demand needs to cool off. They contended that for inflation to go away, wage growth needed to subside and millions of workers needed to be thrown out of work, despite the fact that nearly sixty percent of inflation was attributable to corporate profits. These economists turned out to be very wrong (and to understand why, see our inaugural post). They largely advised against Biden’s fiscal stimulus in the American Rescue Plan, arguing that it would be inflationary, and discounted the IRA, arguing that it would be useless (at least with respect to inflation). These economists did advocate for the Fed’s tightening of monetary policy, which happened, but they wanted it as a means to cool the labor market, which it has only moderately done.

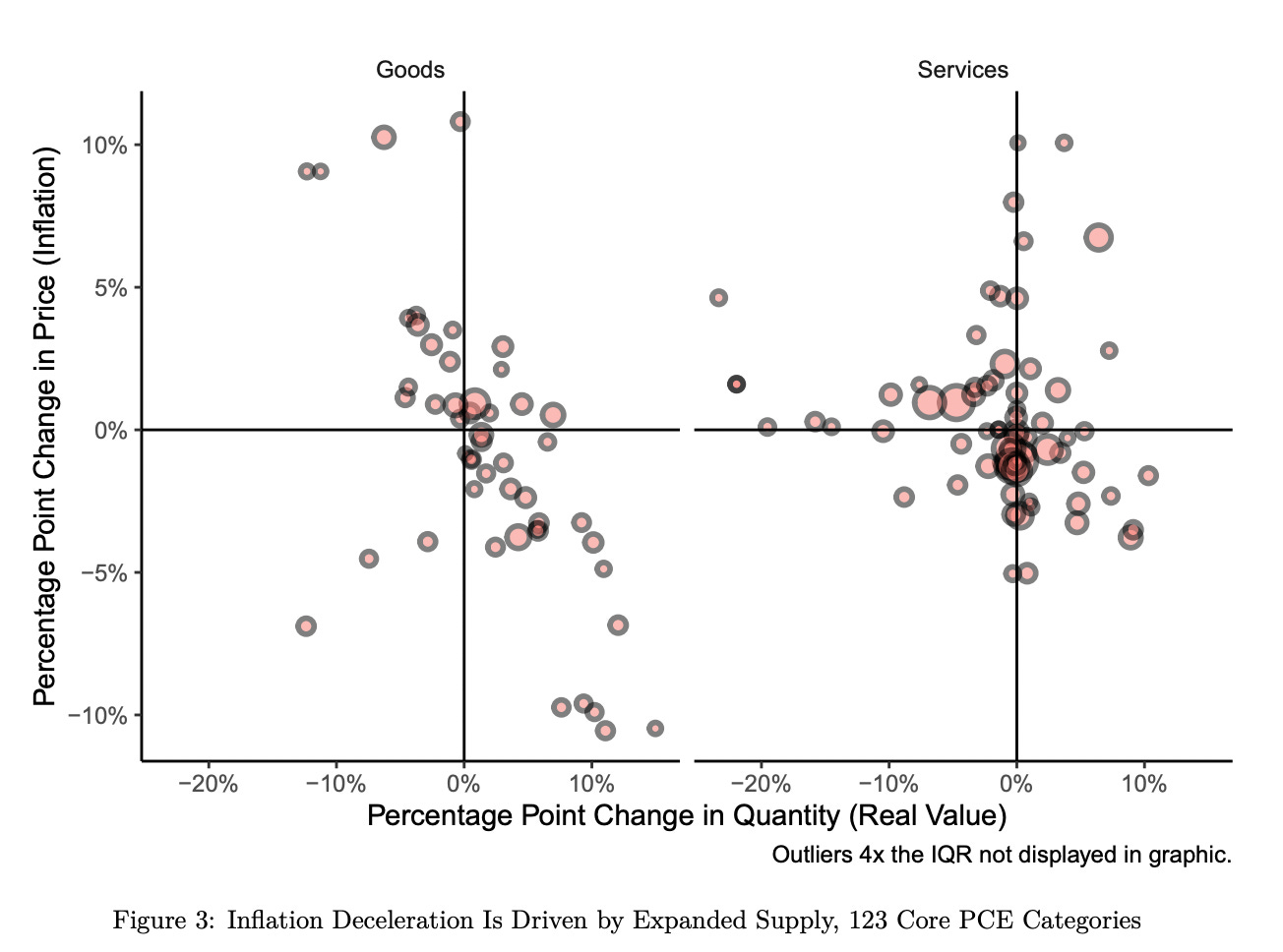

New evidence from Mike Konczal at the Roosevelt Institute helps shed some light on why inflation has gone down contrary to the expectations of many economists. It turns out the large majority of that reduction was driven by increases in supply, not declining demand. Konczal explains:

“Of the core PCE [Personal Consumption Expenditure] categories that saw price declines, weighting by their share of nominal consumption, we see that 73 percent came from supply expansion, while 27 percent came from decreasing demand.”

The results for the service sector are also striking, with 66 percent of price declines attributed to expanding supply.

Annual Changes in Quantity vs. Changes in Price for Core Personal Consumption Expenditure Price Index (PCE) categories

Source: Konczal 2023

To be clear, these findings suggest that the Fed’s monetary tightening played only an ancillary role in reducing inflation. The rapid decline of inflation can primarily be attributed to the overcoming of post-pandemic shocks. So now we need to discuss what permitted us to overcome these supply shocks (and if calling them “shocks” is entirely appropriate).

One hypothesis is that inflation truly was transitory, as several high profile economists, including Janet Yellen and Jerome Powell, alleged in 2021. In this narrative, the economy just needed a longer period of time than expected to fully overcome supply shocks after the pandemic, a position Paul Krugman calls “Long Transitory”. However, champions of this view often struggle to explain why getting all the kinks out of the supply chain took so long.

That leads to another explanation: that inflation was driven by supply chain kinks that were persistent because they were profitable to corporate monopolies. Several major companies recorded record profits in 2021 and 2022, giving them little incentive to fix bottlenecks that were their responsibility. In this telling, a mix of regulatory and antitrust enforcement, threats from the Biden administration, and changing consumer expectations eventually forced monopolies nearer to pre-pandemic pricing norms.

Lastly, persistent growth in consumer spending, fiscal stimulus, and tax credits for business investment —like those in Biden’s American Rescue Plan and the Inflation Reduction Act— may have prompted firms to invest more and ramp up their competition with one another, resulting in lower prices for consumers.

Determining which of these three hypotheses has the greatest explanatory power is a difficult task that economic research is only beginning to catch up with. Too many economists are married to old dogmas, desperate to believe that managing demand is key to bringing down inflation and unwilling to entertain the idea that government regulation, the promotion of competition, and even fiscal stimulus can reduce inflation by increasing the supply of goods and services in the economy.

If Biden can keep the balance of fiscal stimulus correct, promote supply growth, and continue to manage drug and energy prices through a mix of regulation and industrial policy, it would mark a major victory for Bidenomics. Time will tell.

I encountered your Substack via Notes and I'm excited to see that there is another writer bringing in an economics-led perspective to the many social and economic issue we face today!

On the recent inflationary period - yes, it's very interesting how some economists stick so strongly to their priors and are not open to not seeing other ways and other research. I've written quite a bit about the supply driven causes of inflation (https://www.nominalnews.com/p/unintuitive-inflation-supply-wages) and surprisingly these models appear to not be understood by many economists. I'm actually writing about Governor Waller's surprising statement regarding inflation cannot be driven by supply shocks!