What’s Wrong With Gen Z?

The educational, professional, and cultural troubles of our generation

I recently turned twenty-five. In many ways, I am the typical product of my generation. I have a penchant for making a joke of everything, I resent our country’s leadership, and I tend to scroll on my phone when bored in class. Several essays have been published recently trying to decipher why Gen Z is the way that it supposedly is: miseducated, maladjusted, and misanthropic.1 I hope by sharing some autobiographical details I can clear up some of the confusion.

I was born in 2000. When I was just over a year old, two planes slammed into the World Trade Center. Though I never had any personal memory of the attacks, their memory would recur throughout my generation’s childhood. There was the time when our school brought in injured veterans to show off their new prostheses. There was the time when our homeroom teacher triumphantly showed the class a (fake) image of Osama bin Laden’s bullet-penetrated head. And there were the annual showings of a 9/11 documentary which would yield tears from our teachers and bemused jokes from students. Perhaps my first ringing of political consciousness came during the rise of Barack Obama, who seemed to confirm our inclination that the wars being fought to avenge these attacks were dumb.

There was also a striking trend regarding our parents. In middle school, I ate lunch with close friends —about an even split of boys and girls— at a round table that seated eight. Among those eight, I was unique in two ways. I was the only one whose parents did not require them to attend church, and I was the only one whose parents were still married. Religion was associated with Christian support for our nation’s religious war, the rampant homophobia of the time, and our parents’ moral hypocrisy and failed marriages. Today, none of us are married, though a few have come close.

These trends inclined us toward a youthful liberalism. We had seen what the church, war, and traditional family structure had offered our parents, and it wasn’t very compelling. The only political counter-force came from the rise of social media.

Nearly everyone my age remembers begging their parents to let them have a Facebook account and an iPod. Eventually, most gave way and we began spamming each other with FarmVille requests and posts on each other’s walls. While obsessively posting and chasing likes surely warped the mental health of many, I am more familiar with a different popular facet of online culture: browsing content on YouTube that increasingly took a political slant.

By eighth grade, names like Sargon of Akkad, The Amazing Atheist, and Armoured Skeptic were common currency among my male friends. These were regular people, recording videos in their homes documenting the excesses of “social justice” and explaining why it was near impossible for this generation of young men to get ahead.2 Before we called people “woke”, we called them “social justice warriors” and it was the fault of these blue-haired menaces that college campuses were bastions of the far-left, why Islam could not be openly criticized, and why intelligent young men were not living up to their potential.

And their potential seemed high. All of my friends who made an effort in school received high marks. Grade inflation had rendered As easily attainable and the ACT did a better job at testing one’s willingness to prepare for such an exam than it did intellect. These high grades were not proof that we had learned a lot. My school was well-funded with a healthy selection of AP courses, but these courses focused far more on rote retention than developing analytical capability. When I read articles today claiming that undergrads cannot write coherent paragraphs or finish a book, I am not surprised. The people I grew up with were intellectually curious but deprived of a way to pursue that curiosity or develop basic intellectual skills. Instead, they turned to YouTubers, podcasters, and later, TikTok as an outlet.

This haphazard intellectual exploration did a poor job of substituting for a formal education and surely stunted the minds of millions. However, consuming a vast stream of sensational newstainment could yield a strong sense of feeling educated, without education.3

This made college admissions all the more painful for many. Those who had received high marks —which again, was most— and felt hyper-educated by the Internet, often felt as if they were entitled to a place in a good university. Surely these institutions should recognize their intellect. But many of these people failed to appreciate how little of their “studies” would come across in an application and perhaps how unexceptional their level of intelligence really was. Since grades couldn’t be used to parse out academic ability, students stood out by signing up for an absurd amount of meaningless extracurriculars or writing flowery statements of purpose. Some of the most bitter people I know today are those who were disappointed by this process.

Like many friend groups, upon graduation, ours split. A few of my male friends went to work in the building and electrical trades, earning a decent wage and being protected by a union that sometimes disappointed them. Others went to the service sector. The girls nearly all went to college. I went to a nearby state school.

Along with admittance to this school, I was accepted into an additional program for students interested in politics and law. Most of my early friends were drawn from this program, and many were eager to discuss the issues of our day. At the time, Trump had been in office for a year, and our cohort was split between those who supported Trump and progressives who were upset with him and the weak Democratic response to his administration. Perhaps unsurprisingly, our discussions were emotionally charged, though some participants demonstrated a surprisingly good command history for their age and others were at least rhetorically skilled.

For many of us, classes felt of second-order importance. Sure, we were there to be educated, and many of us appreciated that. But with knowledge at our fingertips and friends to test our mettle against, the often dry abstract coursework of economic or political theory seemed less than relevant.4 This impulse obviously went too far at times. I recall several friends regarding me as nerdy or intellectual because I’d leisurely read nonfiction. One eventually labeled me a socialist—a concept I had only passing familiarity with at the time. In some ways, she was probably right.

After graduating we all went our separate ways. Among the conservatives, one went to work for a tech firm, another on Wall Street, and two for Republican politicians. The liberals took up white-collar jobs: a law clerk, an employee for a green energy company, and a financial analyst. I went on to a government job (an economics RA-ship) before bouncing to my current PhD program.

All of them are unmarried, though I know a few attend church. They, like my old high school friends, share the occasional political post on social media though their old passion is muted. They are now busy with their lives, and while many still resent the limitations they hit in life or the way our country and economy are run, they’ve lost their youthful faith in their ability to effect change or get further ahead. For some, endlessly tracking a current event (Covid, BLM, or the war in Ukraine) amounts to a form of escapism and allows one to make their voice heard on important matters, albeit in the void of social media.

In the end, my generation understands that their voice doesn’t matter, regardless of how much political influencers and politicians try to persuade them otherwise. The government is run by our grandparents and the economy is run by our parents, and neither appears ready to cut us in for a share. Of course, this understanding is coarse and flawed. Our government and economy are run by only a small elite subset of our parents and grandparents but older generations’ knee-jerk tendency to defend the existing order and their resentful attitude toward “kids these days” has led much of Gen Z to embrace a generational rather than a class analysis of society.

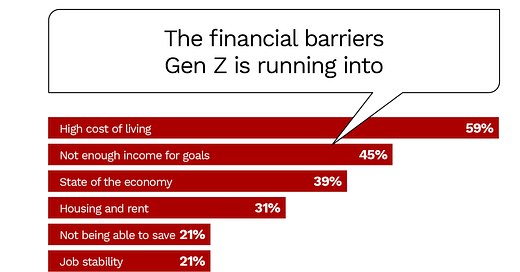

This pessimism has surely made us less hardworking, confident, and disciplined and more anxious on average. It appears our lot will likely be worse than our parents, which makes hard work unattractive.5 Nobody wants to work hard to do worse. And the ability to substantively change society feels out of reach. While the generation that protested the Vietnam War would fairly quickly see some of its political prerogatives adopted by the Democratic establishment, those protesting genocide in Gaza today expect nothing but ire from both political parties. Millions from my generation heard (and believed) former President Biden when he said he had “no empathy”6 for young people struggling today and most feel that President Trump harbors even worse feelings toward us.

Our pasts are colored by the hypocrisies of our parents and our futures promise economic and social stagnation. Many of the cultural anomalies of Gen Z can be understood as an attempt to cope with this lack of moral direction and socioeconomic prospects, either through withdrawal or defiance.

These new anomalies include: incels who cope by lashing out at women; fitness influencers who think we can bulk our way into happiness; mindset gurus who encourage us to see the joy in less; and an over-reliance on therapy and medication, an escape that gives us a new vocabulary to rationalize our discontent and a means of viewing it as biological in origin rather than social. You may notice that all of these coping mechanisms can be exercised alone. And indeed, hopelessness has bred isolation, which in turn breeds more time on our screens and more hopelessness.

Popular media also caters to our desire to escape our dismal cultural environment. First, there’s the massive rise of nostalgia. Recent polls have found large portions of Gen Z longing for eras in which they’ve never lived, and this trend is increasingly reflected in media consumption. Some of our most popular musicians —from Lana Del Ray to Charlie Crockett— openly harken to sounds from previous eras; even young upstart musicians are regularly calling back to earlier times.7 Vintage fashion influencers show off classic menswear or sixties floral designs to adoring young fans. And in the more conservative pockets of social media, tradwives and homesteaders sell a pastoral lifestyle to those who feel like they don’t belong to this generation. Foreign entertainment has also grown in spades, evident by the fact that mine is the first generation where most people know what Manga is. Lastly, the drive toward unhinged sitcoms and even cartoons reflects this trend; the realistic well-written plot and reality television are being displaced by the outrageous, fantastical, and juvenile.

You might also notice that this nostalgia is overwhelmingly from our grandparents’ generation and not our parents’. And perhaps our parent’s cultural icons simply haven’t aged enough to be cool again. But part of it surely reflects my generation’s tense relationship with our parents.

Many of our parents simply weren’t around or didn’t have custody after a messy split, but others became estranged from their kids through a slower deterioration of the parent-child relationship. Almost always, this involves conservative parents and liberal kids, a clashing of the most reactionary living generation with the most progressive.

While our parents largely regard us as lazy and entitled —sometimes carving out an exemption for their own children— we regard them —again, sometimes exempting our own parents— as selfish and emotionally juvenile. Many friends have recounted to me how sick they’ve grown of their parents' inconsiderate nature, political rants (usually filled with mean-spirited trans-bashing, race hatred, or COVID conspiracies), and unfulfilled promises. Eventually, they stop answering calls. A close friend recently recounted a representative anecdote. While he was working from home, he overheard his parents’ reaction to a Fox News segment covering girls on TikTok who were celebrating their childless lives and the freedom it allowed them. Both parents responded nastily, mockingly suggesting, almost bragging, that these women’s lives were purposeless and that they would spend their older years sad and alone. They seemingly did not consider that their son is also childless and of the same age, and I suspect they wouldn’t have held their tongues had one of their daughters been present too. If I were a young woman hearing that from my parents, I suspect I could do little but resent them.

The pathologies of Gen Z are not technologically determined, though tech surely facilitates their expression. Those pathologies are the result of the world our parents built—or continuously justify at our expense. One might be tempted to tell us to move on; that living in rebellion to one’s parents is a juvenile way to live. But that is to miss the point. If we could live in a world different from our parents, many would take action to do so. But lacking political or economic power —or the prospect of acquiring it— Gen Z has coped with the tools that hopeless individuals usually revert to: nostalgia, humor, self-isolation, medication, and apathy. The course of events can change very quickly, and it may be the case that my generation will see its influence grow more rapidly than we expect, but this development appears entirely out of our hands. We are simply riding the course of history while others continue to make it.

Two very good essays inspired this post. The first is Lauren Michele Jackson’s “The End of Seriousness” in The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-lede/the-end-of-seriousness. The second is Hilarious Bookbinder’s Substack post on today’s average college student.

The success of these amateurs in turning young men to the right is hard to understate. Their success almost surely helped inspire the several millions of dollars that conservative donors have invested in online media personalities. The new generation of online right-wing personalities —figures like Ben Shapiro, Dave Rubin and Charlie Kirk— are certainly more polished, though also more forthright in their conservatism, than the figures my friends and I grew up watching.

This was true across the political spectrum as nearly all of us were distrustful of or bored by print and television news.

Many classmates expressed these feelings to me. I usually enjoyed my coursework, excepting mathematics, but often felt at unease with the limitations and structures built into my courses. Consequently, I skipped more than a few classes to read independently.

I will save more purely economic analysis of intergenerational inequality for another day. For now, I’ll simply note that I do not believe the widespread perception that the current young generations are not keeping up with their parents is not merely a product of delusion.

“Biden Doesn’t Want to Hear Millennials Complain: ‘Give Me a Break’.” Newsweek. January 12, 2018. https://www.newsweek.com/joe-biden-says-millennials-dont-have-it-tough-780348

Anyone seeking out new young artists on TikTok or Instagram Reels has likely found several prominent examples. Two of my favorites are Belle Frantz, who resembles Loretta Lynn in voice and appearance, and Paige Fish who similarly resembles Stevie Nicks.

I'll be 60 this year. So that makes me a leading edge Gen Xer. Around 1990, when I was working two jobs and hoofing it all over town because I didn't have a car, I didn't much care for the slacker label affixed to my generation by the boomers. So I have been careful not to give the younger generations shit about not wanting to work or whatever. When I was 20 years old and rented my first apartment, it was $250 a month, and I was being paid $200 a week. It was at least manageable. The cost of living now is insane, and I don't know how young people do it.

Thank you for sharing this thoughtful and reflective essay. As a late boomer, I felt informed not condemned by the tone of the writing which opened up doors for thoughtful sharing between generations. In this spirit, I hope, may I suggest that all of us are the products of social environment in which we developed as people. In my case, I have had a privileged life in a WEIRD country during a time of “progress” and a growing economy fuelled by billions of person years of work derived from fossil fuels. I thought I was well educated and well informed, but, although not unaware of the downsides of this western economic system, it is only in the years since Covid that I have realised how blinkered my view on reality was. Now, I know that my life has been largely wasted chasing false gods that were societally determined. Most of my generation and that following are likely to be in the same boat. I seek not to avoid responsibility for trashing the biosphere and your futures but, in the spirit of your words, to explain how blind we have been.

Our “developed” social and economic system is a human construct that is fundamentally broken, flawed and corrupt at its very core. We knew this from the seventies on, but ignored the warnings. This system will soon break down and there are many signs that the “Great Simplification” (sensu Nate Hagens) has begun. Your generation will bear the brunt of this, for which I beg forgiveness in advance. But you are also the generation which can build something better, more grounded and more socially cohesive.

Obtain the power you need, organise via the social media systems you are expert in and give yourselves a future which you can believe in.