Can Price Controls Work?

Evidence continues to mount in favor of the greedflation hypothesis. Does that mean price controls can work?

As we’ve covered previously, increasing evidence is mounting suggesting that the primary cause of inflation during the post-pandemic reopening was excessively large corporate profits. In industry after industry, profits reached record heights in 2021 and 2022 while prices steadily increased. In short, firms were not merely passing onto consumers their increased labor and input costs, but netting larger margins. In common parlance this position has been dubbed greedflation, but that is a bit of a misnomer. It’s not that corporations became more greedy post-pandemic; it’s that they had greater opportunities to exercise their greed by charging larger markups thanks to strong post-pandemic demand, the tightening of supply chain bottlenecks, and society’s general patience with firms during a hectic time. While originally panned by most of the economics profession, as passions have cooled and evidence mounted, the greedflation theory is being given its due.

However, one of the most prominent proposed solutions to greedflation remains on the sidelines. One of the earliest proponents of the greedflation theory, Dr. Isabella Weber, convincingly argued that in an economy where inflation is primarily driven by increasing markups, a set of “strategic price controls” would be a better counter-inflationary strategy than the Fed’s preferred tool of interest rate hikes. Weber’s proposal was met with skepticism or condescension by the vast majority of the economic profession. Here’s what some of the biggest names in economics had to say:

“Effective price controls, by definition, would reduce price increases, but they would most probably create other huge distortions.” -Daron Acemoglu

“Wage and price controls in the early 70s did little good.” - Joseph Altonji

“Price controls can of course control prices -- but they're a terrible idea!” -David Autor

“As deployed in the 1970s? In the 1970s they were not particularly effective.” - Barry Eichengreen

And these figures are no conservatives. Across the political spectrum, price controls are generally regarded as ill-advised. In this post, we’ll discuss the economic theory and historical evidence that drive contemporary opinions about price controls, and why the post-pandemic recovery may have been the perfect moment for them.

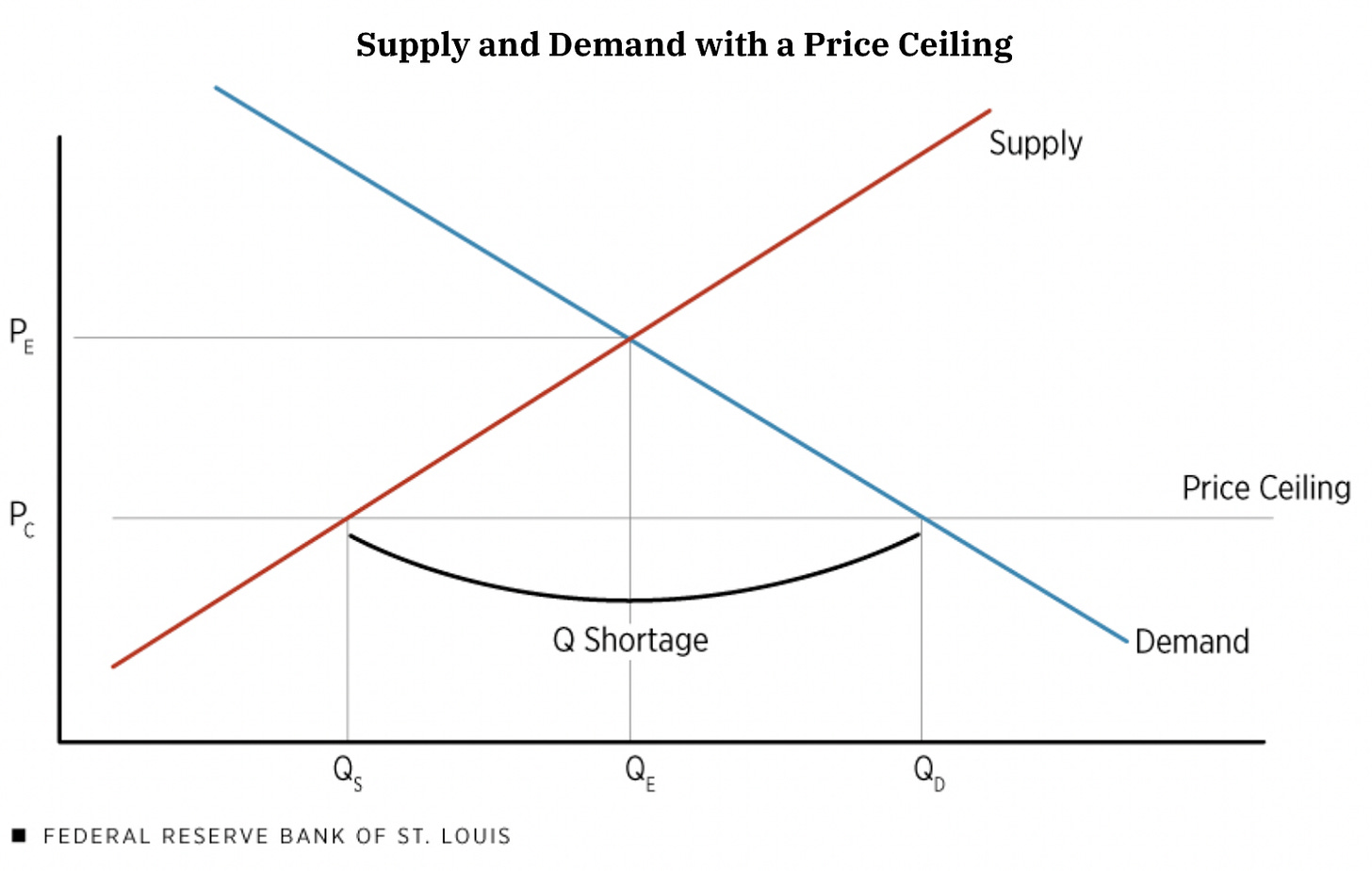

Price controls are poorly regarded by most economists for several reasons. First, under perfectly competitive conditions, a price ceiling that is below the going market price for a good will necessarily produce shortages. If a well-meaning regulator imposes a below-competitive price ceiling of $2 per gallon on gasoline, then some firms in the market will be forced to accept losses, scale back production, or exit the market entirely. While gasoline may have become more accessible for those lucky enough to buy it for $2, the amount of people able to get gasoline in the first place will shrink due to decreased supply.

Second, price ceilings can create distortions across the economy that promote inefficiency. This is because a single individual (or government agency) in charge of price setting is incapable of accumulating and processing the vast amount of data relevant to pricing ingested by the dozens of firms in a supply chain whose non-coordinated actions come to determine the prices of goods in a free market. This criticism was first formalized by Freiderich Hayek, who spent much of his career waging the Socialist Calculation Debate, where he contended that the extent of human ignorance made it impossible for the government to set efficient prices. In his paper, “The Use of Knowledge in Society”, he explained:

“Fundamentally, in a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coördinate the separate actions of different people in the same way as subjective values help the individual to coördinate the parts of his plan.”

While rapid advances in computing power and information technology have somewhat allayed this concern for some observers, the general opinion among economists is that we are still far too ignorant to foresee all the consequences of playing around with individual prices. To borrow Donald Rumsfeld’s overused phrase, there are simply too many “unknown unknowns.”

Similarly, price controls can cause what economists call allocative inefficiency, a distribution of goods and services that fails to correspond to peoples’ willingness to pay for them. With respect to production, the shortages and rapid changes in relative prices caused by price controls can create distortions in unanticipated sectors of the economy, causing more havoc than stability. For consumers, a lapse in allocative efficiency means that the consumers willing to pay the most money for a good might not be the ones who get it. This may result in people who are less well off getting increasing access to necessities, or it could result in people who genuinely value a good less getting it instead of those who value it more. Without goods going to the highest bidder, another method of distribution must be adopted. Historically this has taken the form of rationing or some sort of first-come-first-serve style of distribution.

Lastly, it’s often argued that price controls will be rendered ineffective by firms that will decrease the quality of goods sold or invent new schemes to charge consumers higher prices in real terms. Here’s an explanation from economic historian Hugh Rockoff:

“One [method to evade price controls] is the tie-in sale. During World War I, for example, in order to buy wheat flour at the official price, consumers were often required to purchase unwanted quantities of rye or potato flour. Forced up-trading is another. Consider a manufacturer that produces a lower-quality, lower-priced line sold in large volumes at a small markup, and a higher-priced, higher-quality line sold in small quantities at a high markup. When the government introduces price ceilings and causes a shortage of both lines, the manufacturer may discontinue the lower-priced line, forcing the consumer to "trade up" to the higher-priced line.”

In some industries the potential to decrease the quality of goods is a real concern (The quality of clothing, for example, notoriously deteriorated after price controls were introduced during World War 2), but for several industries such rapid changes in the quality of goods are not feasible. Branded firms would also be ill-advised to temporarily reduce the quality of their products given the reputational damage they might consequently suffer. Additionally, the potential for tie-in arrangements is far smaller than in times past. Rockoff cites an example from America’s price controls during World War One, but since then using these sorts of arrangements to charge higher prices has been interpreted as illegal under America’s antitrust laws.

Careful readers may have noticed that most of the aforementioned alleged harms caused by price controls were predicated on the assumption that the firms who suffered controls were engaged in rigorous competition. If firms had market power and were able to set prices, instead of passively accepting whatever price the market granted them, then the efficient pricing ability of firms is severely diminished, as even Hayek himself recognized:

“The price system will fulfill [its] … function only if competition prevails, that is, if the individual producer has to adapt himself to price changes and cannot control them.” (See Hayek 1944)

When industries are largely concentrated and prices are significantly above marginal cost, price ceilings can (at least in theory) be imposed without creating shortages or the distortionary effects outlined above. In fact, price controls may promote greater efficiency by bringing prices nearer to their competitive level.

Furthermore, enforcing price controls is much easier in concentrated industries. There are fewer firms to monitor, and because they set prices they’re easier to police relative to a highly competitive industry. In his popular book on the administration of price controls, John Galbraith, an administrator for the largely successful WW2-era Office on Price Administration explains:

“Specifically, demand in the imperfectly or monopolistically competitive market is subject to an informal control by the seller which is frequently the effective equivalent of rationing. The purely competitive market lends itself to no such control.”

And since these large firms rarely interact with consumers when making pricing decisions, there’s little room for consumers and producers to haggle and agree to a higher price in violation of the ceiling. While you may negotiate at your local farmers’ market, you don’t negotiate with Walmart. In the words of Galbraith, “It is relatively easy to fix prices that are already fixed.”

These factors make enforcement much simpler and the likelihood of black markets emerging slimmer. They also explain the relative ease with which the prices of milk and primary metals, both highly concentrated industries, were controlled by Galbraith relative to the administrative difficulties posed by the prices of vegetables and secondary metals, both highly competitive industries (See Galbraith 1952).

Another factor critical to the success of Galbraith’s controls was the excess slack in the American economy following the Great Depression. By lowering prices, ceilings naturally create an increase in demand. To prevent the pressure on ceilings from getting too great, it is helpful if there are people waiting in the wings ready to produce more and meet that new demand (or a rationing system in place to manage said demand).

Thanks to the WW2-era expansion in production afforded by this slack in the economy and the considerable time it takes for firms to manage their given inventories and change their business strategies in response to controls, Galbraith was afforded crucial time to carefully hone his controls. As he explains:

“Repeatedly the agency [OPA] was able to forestall upward thrusts in prices and hold these prices, while for several months — sometimes a year or two — supply remained abundant. This period of grace was invaluable. While it lasted, the regulations could be perfected: a simple “freeze” of prices could be translated into a workable price schedule.”

At this point, you may notice that the conditions I’ve described under which price controls can work sound very similar to the conditions of the American economy during the post-pandemic reopening. Industry was very concentrated and undergoing further consolidation, experiencing a massive wave of mergers and a wider dissemination of information-sharing technologies that drive prices above competitive levels. Much of the early inflation was attributed to “bottlenecks”, almost definitionally a symptom of concentrated industries lodged in supply chains. Price controls could have both mitigated their effects on the general price level and incentivized firms to fix their bottlenecks more quickly (as they’d be able to extract less profits from them). The labor market was also full of slack due to the massive number of layoffs that took place during the pandemic (Getting Americans back to work, and the increase in production that followed, played a large role in reducing inflation.) If controls were imposed, shortages would have only needed to be held off for a few months, maybe a year tops, before price controls could have been done away with and we could have enjoyed a much less volatile reopening with supply chain kinks already worked out. That said, it’s safe to say that price controls are no magic wand. Such an approach would not be particularly effective for goods sold under highly competitive conditions or for goods like oil where international production plays a massive role in determining domestic prices.

Given all this, why was there so little support for price controls? As previewed above, most professional economists’ views of price controls are negative, prejudiced by the weight of history. Even Galbraith admitted that:

“Prior to World War II there did not exist in economic history, so far as I am aware, an important experiment in the public regulation of prices or wages which, in the consensus of its interpreters, was thought to be a brilliant success or even a success.”

In the minds of most economists, price controls are associated not with the success of the OPA’s World War 2 experience, but with the failures of New Deal-era price fixing and the cynicism of Richard Nixon. The price ceilings implemented by FDR were primarily done under the auspices of the National Recovery Administration (NRA) through industry-wide codes which were so haphazard but business friendly that its ceilings rarely had a significant effect. After a few short years the supreme court ruled the NRA unconstitutional and the whole experiment died, though not without leaving a bad taste in the mouths of many economists and businessmen who felt it too close to socialism. Nixon’s price controls trigger even worse memories, likely because many of our preeminent economists lived through them. The biggest taint on Nixon’s price controls are that they are forever associated with the political cynicism of Richard Nixon, perfectly timed to favor his reelection and then recklessly abandoned with no regard to what would follow. Nixon’s price controls were paired with loose monetary policy (economically illogical, but a politically savvy way to goose the economy before the 1972 election), leading to a surge of inflation immediately after the controls were ended. Since then, price controls have been viewed as the tools of economically illiterate populists and cynical opportunists.

Most commentators on price controls, even their most vocal advocates, would admit that the historical record of price controls is dismal. Limited human knowledge, real material constraints, the emergence of black markets, and political opportunism dulled their effectiveness and distorted economic incentives. Yet, it’s also clear that they’ve worked fairly well in some instances since the rise of concentrated industries, particularly in the context of World War 2. Even papers quite critical of price controls tend to include a caveat noting that they “may make a positive contribution by calming [inflationary] fears” or that there are situations in which “temporary controls may be effective.” Despite the economic community’s apprehensions, it seems that the reopening following the pandemic likely was one of those situations. The price increases in several industries were driven primarily by excessive margins in concentrated industries; there was tons of slack in the labor market; and shortages likely could have been held at bay. For years, economists scoffed at the idea of greedflation, though it’s becoming increasingly accepted. Now, they need to come to grips with how greedflation can be solved the next time it comes around. Price controls are at least worth serious consideration.