An Exhaustive Review of Thomas Sowell’s New Book

Sowell's lectures on race, inequality, and knowledge leave a lot to be desired. Instead of illuminating reality on these topics, Sowell wages battle against unnamed "social justice" adversaries.

Thomas Sowell’s latest book, “Social Justice Fallacies,” is an opportunity for the elderly economist to caution us against errant thinking. He’s concerned with the excesses of those advocating for “social justice” whose intellectual hubris, intolerance of dissent, and hesitancy to subject their ideas to empirical testing, lead them to a false confidence that often produces catastrophic results. As we’ll document, Sowell may be engaging in a bit of projection, but that’ll become clear in due time.

This book largely covers the topics of race, inequality, and knowledge (which fill chapters 2, 3, and 4 respectively). Chapters 1 and 5 are bookends that blend all of the topics together. We’ll cover each chapter one at a time, going claim by claim.

CH1 “Equal Chances” Fallacies

Sowell opens his first chapter with a criticism of the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau's distinction between “the equality which nature established among men and the inequality which they have established among themselves.” Sowell vehemently disagrees with this idea, arguing that we are not all equal in nature and in fact “people from different backgrounds do not even necessarily want to do the same things.” Assumptions like Rousseau’s are the essence of social justice fallacies:

At the heart of the social justice vision is the assumption that, because economic and other disparities among human beings greatly exceed differences in their innate capacities, these disparities are evidence or proof of the effects of such human vices as exploitation and discrimination.

Sowell then peppers us with a few examples. Jews dominated the banking sector in the Ottoman Empire while being a minority; Germans are known for their brewing of beer; Canadians are more represented among hockey players than Californians. Can these tendencies really be explained by discrimination? Of course not. As Sowell explains, the climate, geography, and culture of the places we live in play a critical role in determining our preferences and the pastimes we are exposed to.

Even pure happenstance can favor some groups over others. First-born children are far more likely to win the National Merit Scholarship, Sowell notes, likely because they receive the undivided attention of their parents in their most formative years. This leads Sowell to ask:

Can anyone seriously believe that children spending their formative years growing up in [very different] homes…are likely to be the same as others in school, on a job, or elsewhere?

The answer is no. I don’t think anyone seriously believes that. If Sowell thinks that people who hold the “social justice vision” hold that belief, he should cite them expressing it. The closest he comes to doing so is disparagingly citing a headline that poses the question: “Why are Black and Latino people still kept out of the tech industry?” Sowell paints this article as “A typical example of equating differences in demographic representation with employer discrimination.” But, if you were to read the article, you’d see that it does no such thing. In fact, it doesn’t even reference employer discrimination as a possible answer to its titular question. The answer to its question it gives the most credence to is the following:

Tech leaders have often pointed to a “pipeline problem” to explain away the lack of Black hiring and promotion. But in 2016, 8.6% of graduates with a bachelor’s degree in computer and information science were Black and a little over 10% were Latino, according to the National Center for Education Statistics…

Many tech companies also rely heavily on referrals from current employees, a system that is not unusual in business but which can reinforce the network effects. “Who do you typically refer? People that look and act and dress and speak and do the same things that you do,” Williams said.

This behavior among tech firms may have the same effects as discrimination (disparate impacts), but it’s not necessarily discrimination. (Sowell would not consider this conduct discrimination.) Essentially the article suggests that Black and Hispanic workers in the tech space may be struggling to actualize their potential because of the reference system. Sowell turns to this topic too:

Among the many factors that can prevent human potentialities from producing equally developed capabilities are factors over which humans have very little control — such as geography— and other factors over which humans have no control at all, such as the past.” Shortly after, he mentions: “The equality of different groups of human beings — presupposed by those who regard disparities in outcomes as evidence or proof of discriminatory bias — might well be true as regards innate potentialities. But people are not hired or paid for their innate potentialities.

Again, this is true, but it exposes a critical flaw in Sowell’s argument. He never contends with the idea that discrimination (or past discrimination) may play a role in limiting the abilities of some groups to actualize their potentialities into developed capabilities, like we discussed in the example above. Sure, an employer may not explicitly discriminate on racial grounds, but what role did societal factors play in choosing what candidates might turn up in front of him and the experiences on their resumes. Might discrimination have shaped the educational opportunities available to different groups of people in different ways? Shockingly, Sowell doesn’t consider this. It’s a major omission given the large dialogues about structural or systemic racism that advocates of social justice have been discussing in the last several years.

Several times Sowell expresses his support for “equal opportunity,” but that seems to begin and end at mere equality under the law. If it so happens that Black schools are horribly underfunded due states’ decisions to fund them primarily based on local property taxes, so be it. Apparently, getting access to an education as decent as everyone else is not important to having an “equal opportunity.” I’m reminded of A.B. Atkinson’s famous quip that it’s difficult to determine where equality of opportunity begins and equality of outcome begins.

In addition, while Sowell considers several causes for why groups may experience different outcomes, the one he fails to consider is discrimination. Ironically, he mentions some disparities that have historical roots in discrimination (like the Jewish presence in finance), but these are only ahistorically marveled at as examples of minorities in advantageous positions. We’ll see more of how Sowell handles (though mostly ignores) discrimination in chapters to come.

Sowell then spends several pages discussing why nations developed differently. He doesn’t commit to any one thesis, and instead gives a decent survey of cultural, geographic, demographic and other explanations. It’s all ho-hum and its only purpose is to demonstrate the stupidity of the “invincible fallacy that only human bias can explain different economic and social outcomes among peoples.” I still don’t know who believes that, aside from (allegedly) Rousseau in that one sentence fragment. By the way, Rousseau was referring to the contrast between the relative equality of man in the “state of nature” and the relative inequality of man after the advent of civil society and its protection of property rights, not the fact that there were more Germans brewing good beer than Italians.

Sowell closes this chapter with some controversy:

We might agree that “equal chances for all” would be desirable. But that in no way guarantees that we have either the knowledge or the power required to make that goal attainable, without ruinous sacrifices of other desirable goals, ranging from freedom to survival…Do you want airlines to have pilots chosen for demographic representation of various groups, or would you prefer to fly on planes whose pilots were chosen for their master of all the complex things that increase your chances of arriving safely at your destination?

This leads one to ask if this is a genuine tradeoff society is facing. Former Fox News host Tucker Carlson certainly agrees with Sowell:

This is what happens when you decide that identity is more important than aptitude in something critical like aviation. At some point, many people are going to die because of this.

Despite this fear mongering, there have been no fatal airline crashes involving a major US airline for nearly fifteen years. The main way new Black pilots are being brought into the aviation industry is through exposure and instruction that was previously unavailable in their communities. For example, Omar Brock, a Black pilot from the Atlanta area, started a foundation to help get more Black youth interested in aviation:

We go out into the communities of color, and we start with exposure…Then we provide free resources through ground school curriculum and making it available for free.

Contrary to Sowell and Tucker’s concerns, Black pilots face the same tests, required flight hours, and regulatory hurdles as everyone else. There’s no evidence that they’re being favored over anyone else. And frankly, neither Sowell nor Tucker can confidently allege otherwise. They can only obliquely allude to the possibility of it (and the horrible consequences that would allegedly follow.) The whole debate is nothing but abstract theorizing at best. Is there a serious tradeoff between identity and competency? No evidence is apparent in this case. Besides, with the current shortage of pilots, there’s no latitude for picking identity over competency. I’d wager that an overworked pilot is more dangerous than a Black one.

Sowell also spends a lot of time talking about “reciprocal inequalities,” i.e. different groups being good at different things. He says it’s “hard to find any ethnic or large social group that has no endeavor in which it is above average.” That might lead one to ask if Black pilots might have some particular talents or insights that are going unutilized that could not only diversify the aviation industry, but improve it with the new reciprocal inequalities they bring. But this idea isn’t entertained. Promoting diversity and the pursuit of merit are always framed as antagonistic goals.

Sowell also spends this chapter lamenting that “Many assumptions and phrases in the social justice literature are repeated endlessly, without any empirical test.” You may have noticed that Sowell has applied no empirical tests so far, but that’s going to change in chapter 2 and introduce us to some of Sowell’s dodgy sourcing practices.

CH2: Racial Fallacies

Sowell opens this chapter as follows:

Racial and ethnic issues have often produced vehement assertions in various times and places around the world. These assertions have ranged from the genetic determinism of early twentieth-century America —which proclaimed that “race is everything” as an explanation of group differences in economic and social outcomes— to the opposite view at the end of that century that racism was the primary explanation of such group differences.

This sets the tone for the entire chapter, which Sowell will spend tirelessly trying to draw equivalences between the Progressives of the early-twentieth century and the Progressives of today (all without citing a single contemporary Progressive). Before getting to that, Sowell needs to note that differences between groups happen for all sorts of reasons, and while discrimination can be a cause, it should not preclude all other causes (Again, who disagrees?)

Sowell seems to think that the fact that Asian Americans perform above whites on several metrics proves that racial discrimination is irrelevant:

The 2020 U.S. census showed that Asians of Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Korean ancestry had higher incomes than whites. … Is this the “white supremacy” we hear so much about?

In fact, this is supposedly such a gotcha that it’s printed on the back cover of the book. And Black people can’t be affected by discrimination either. After all, “There are also thousands of black millionaire families, and even several black billionaires, including Tiger Woods and Oprah Winfrey.” Sowell also notes that Black married couples have lower poverty rates than white single-parent families: “If “white supremacists” were so powerful, how could this happen?”

Sowell seems to believe his opponents think that all-powerful white supremacists can mete out poverty to anyone who draws their ire. By assuming that his adversaries think that literally all variance between races is the result of discrimination, he presents them as believing things that are downright silly and disproven by the mere existence of Oprah. And this isn’t a one-off. Shortly after, he points out that the school delinquency rate in different Black Chicago neighborhoods in the 1930s ranged from 2 to 40 percent. He emphasizes “these were disparities within the same racial group,” as if we’re supposed to be surprised that all Black people don’t behave identically. We’re then treated to the shocking news that poor white counties also exist. It can at times be hard to tell if Sowell is being condescending or if he really thinks that his adversaries (or his readers) are this simple-minded.

Sowell then laments the legacy of Tocqueville, who “attributed differences between Southern whites and Northern whites to the existence of slavery in the South.” Sowell brushes off that explanation, contending that:

[T]he very same range of differences existed between the ancestors of white Southerners and the ancestors of white Northerners when they lived in different parts of Britain, before either of them had ever seen a slave.

Sowell’s source for this is Southern historian Grady McWhiney who contends that the differences between the regions can be traced back to the fact that predominantly Celstish migrants to the American South were distinct from the primarily Anglo-Saxon migrants to the North. This view has been criticized by historians for significantly overestimating the number and influence of Celtic people in the South. It may be worth noting that McWhiney has been called “a godfather of… the neo-Confederate movement” which is quite the person to cite when trying to explain away the relevance of slavery. Regardless, Sowell is constantly peeved when disparities are described as “a legacy of slavery,” even if he never bothers to examine the histories or data that drive such claims. The one exception is when discussing out-of-wedlock births:

Internationally, in the twenty-first century, there are a number of European nations where at least 40 percent of the births are to unmarried women — and these nations have no “legacy of slavery”.— But they have expanded welfare states.

Out-of-wedlock births have risen rapidly for all races since the 1960s, but they were far more common in Black families for as far back as data is available. In 1952, Black children were roughly four times more likely to be born out-of-wedlock as white children. Now, they are only twice as likely. Sowell doesn’t have anything to say on this.

Now it’s time to talk about Progressives. Sowell says that the Progressives of the early twentieth-century promoted “genetic determinism— the belief that less successful races were genetically inferior,” while contemporary Progressives “took an opposite view on racial views. Less successful races were now seen as being automatically victims of racism.” But, they still have a lot in common. “Similar views on… the role of government, environmental protection and legal philosophy.” Both groups of Progressive also “expressed utter certainty in their conclusions… and dismissed critics as uninformed at best, and confused or dishonest at worst.”

From here on, we’re treated to a brief history of the Progressive movement and the racist things some of its most prominent members said. Sowell walks us through Professor Edward A. Ross’s book on “race suicide” (an earlier forerunner to the Great Replacement Theory), Keynes’s membership in Cambridge’s eugenics society, and a bunch of detestable quotes by famous intellectuals from that time. Sowell makes sure to continuously note that all of these people were “on the political left” and somehow predecessors to today’s Progressives. And in a way, they were. The early Progressives wanted to embrace reform and social policies to make the country more livable for white people; today’s Progressives hope to do so for all people. Sounds pretty good, right? No, Sowell says, because for these new Progressives “statistical disparities between blacks and whites, in any endeavor, have usually been sufficient to produce a conclusion that racial discrimination was the reason.” Sowell does not provide any sources or examples of modern Progressives doing this.

The closest he gets is trying to dispute the thesis that Blacks are “the last hired and the first fired” during economic downturns because of discrimination. The trend is demonstrable, though its causes are under-studied. Sowell notes that this trend can’t be the result of racism because whites tend to be fired before Asians. His source is a piece from the WSJ op-ed page. But that op-ed is only talking about the downturn from 1990-91, and it doesn’t say anything about whites losing jobs before Asians. Citing an analysis of 35,000 companies, it says that “Blacks lost a net 59,479 jobs at these businesses during the recession.” Meanwhile, Hispanics, whites, and Asians all gained net jobs.

Sowell also says that:

outraged demands in the media, in academia, and in politics that the government should “do something” about racial discrimination by banks and other mortgage lenders… [led the government to force] mortgage lenders to lower their standards…This made mortgage loans so risky that many people, including the author of this book, warned that the housing market could “collapse like a house of cards.”

But this is not an accurate description of what happened or what Sowell had warned. Here’s the relevant paragraph from Sowell’s WSJ op-ed:

Interest-only loans represent speculation on both rising personal income and rising housing prices. If either income or housing prices fail to rise at the expected rate, this whole financial arrangement can collapse like a house of cards, when higher mortgage payments become due and cannot be paid. Since interest-only loans can be expected to have adjustable interest rates, a national rise in interest rates will tend to raise these mortgage rates as well, driving up the monthly payments, even before any payments on principal are due, and exacerbating the rise in mortgage payments after the initial interest-only period has passed.

Sowell’s right that interest-only loans were speculative, and they did in fact play a major role in bursting the housing market bubble, but he’s wrong that the widespread adoption of interest-only loans was the result of the government forcing banks to do something about racial inequities. Interest-only loans (along with adjustable rate loans and all their cousins) were legalized under the 1982 Alternative Mortgages Transactions Parity Act. The Reagan administration wasn’t supporting its passage in the name of racial equity, but in the name of deregulation of business. That said, these sorts of alternative mortgages did not take off until the mid-2000s, again, not because the government forced them to in the name of equity, but because investment banks were hungry for whatever mortgage-backed securities they could get their hands on, even if the underlying mortgages were junk. Since the 2008 crisis Progressives, through both Dodd-Frank and the CFPB have worked to regulate these mortgages more tightly, albeit with little help from Sowell’s intellectual allies.

Sowell has one more example to demonstrate why the social justice drive for racial equity is misguided:

It has been much the same story with student discipline in the public schools. Statistics show that black males have been disciplined for misbehavior more often than white males. Because of the prevailing preconception that the behavior of different groups themselves cannot be different, this automatically became another example of racial discrimination — and literally a federal issue. A joint declaration from the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of Justice warned public school officials that they wanted what they characterized as a racially discriminatory pattern ended.

However, if you read the declaration in question, you’ll quickly learn that Sowell has mischaracterized it. The declaration is about the overuse of suspensions and expulsions for even minor behavioral infractions and its impact on the quality of education students are receiving. The closest the letter gets to mentioning discrimination is here:

No student or adult should feel unsafe or unable to focus in school, yet this is too often a reality. Simply relying on suspensions and expulsions, however, is not the answer to creating a safe and productive school environment. Unfortunately, a significant number of students are removed from class each year—even for minor infractions of school rules—due to exclusionary discipline practices, which disproportionately impact students of color and students with disabilities.

But the letter does not attribute this disproportionate impact to discrimination. In fact, it doesn’t attribute it to anything, because the primary purpose of the letter is not to discuss discrimination or racial inequities. And the letter hadn’t “warned public school officials” to end this pattern, or do anything for that matter. It just announces the “release of a [free and voluntary] resource package that can assist them, as well as schools, in crafting local solutions to enhance school safety and improve school discipline.”

Sowell ends by explaining that perhaps the “widest consensus on racial issues, across racial lines” was MLK’s speech at the Lincoln Memorial where:

he said that his dream was of a world where people “will not be judged by the color of their skin but the content of their character.” His message was equal opportunity for individuals, regardless of race. But that agenda, and the wide consensus it had, began eroding in the years that followed. The goal changed from equal opportunity… to equal outcomes.

It hardly needs stating that there was not a wide consensus on racial issues during 1963. In May 1963, a few months before the “I have a dream” speech, MLK had a 41% favorability rating among the American public (37% unfavorable.) To suggest that this “wide consensus… began eroding” as a result of the movement’s expanding vision, instead of, say, racial backlash to the movement’s successes is revisionist at best. It’s also worth noting that to achieve his dream of equal opportunity, MLK believed affirmative action was necessary. In his words: “A society that has done something special against the Negro for hundreds of years must now do something special for the Negro.”

Ch3: Chess Piece Fallacies.

We begin chapter 3 with a novel development: Sowell cites someone he’s criticizing that actually can be described as at least tangential to modern Progressivism: John Rawls. But the citation is not exactly illuminating:

In much of the social justice literature, including Professor John Rawls’ classic A Theory of Justice, various policies have been recommended on grounds of their desirability from a moral standpoint… for example Rawls referred to the things that “society” should “arrange.”

But Sowell doesn’t like this because he thinks people like Rawls treat society as a chess board, where pieces can be moved freely without disturbing other ones on the board. In short, they don’t put serious effort into anticipating the ramifications of the policies they advocate. Sowell calls this “The exaltation of desirability and neglect of feasibility.” He continues:

Neither social justice advocates nor anyone else can safely proceed on the assumption that the particular laws and policies they prefer will automatically have the results they expect, without taking into account how the people on whom these laws and policies are imposed on react. Both history and economics show that people are not just chess pieces, carrying out someone else’s grand design.

For example, Sowell says that “The confiscation and redistribution of wealth… is at the heart of the social justice agenda.” But, the rich are not pieces on a chessboard, so they’ll react to these efforts, and their reactions might have unforeseen consequences. For his first example, Sowell cites a Maryland tax hike on those who earn more than $1 million in income. But, after the tax took effect:

[The] number of such people living in Maryland had declined from nearly 8,000 to fewer than 6,000. The tax revenues which had been anticipated to rise by more than $100 million, actually fell instead by more than $200 million.

Sowell’s source for this claim is another WSJ op-ed, which does report these figures, but then immediately qualifies them:

Yes, a big part of that decline results from the recession that eroded incomes, especially from capital gains. But there is also little doubt that some rich people moved out or filed their taxes in other states with lower burdens. One-in-eight millionaires who filed a Maryland tax return in 2007 filed no return in 2008.

From this admission alone, a maximum of 1,000 millionaires (half of Sowell’s estimate) may have taken steps to change their tax jurisdiction as a result of the new tax. Some of these 1,000 surely died or moved. It turns out that the Great Recession played a much bigger role in reducing income tax receipts from the rich than raising their marginal tax rate from 4.75 to 6.25 percent, but Sowell doesn’t mention this. In fact, in 2009 the number of millionaire tax returns filed dropped by a greater percent nationwide than it did in Maryland!

Source: Tax Foundation

Sowell then makes the same mistake again:

Likewise, when Oregon raised its income tax in 2009 on people earning $250,000 a year or more, its income tax revenues also fell instead of rising.

Again, it’s not shocking that tax revenues fell during the greatest recession in the last half-century. It happened in 45 out of the 50 US states, most of which didn’t raise taxes (and some of which passed tax cuts!) Even one of the Journal’s own employees felt compelled to speak out against this obvious nonsense, noting:

That demographics and economics matter more than taxes in increasing and retaining wealth may seem like an obvious point. Still, it is one that seems to get lost in the increasingly emotional debate over taxing the wealthy.

Sowell then contends that “Conversely, a reduction in tax rates does not automatically result in a reduction in tax revenues.” This is just the Laffer Curve and Sowell’s argument is one we’ve addressed before. He looks at countries that are experiencing economic growth and then pass a tax cut. That economic growth produces additional revenues, sometimes more revenue than the tax cut costs, and Sowell uses that to presume that the tax cut (not the growth) is responsible for the gains in tax revenue.

Sowell laments that:

For some —including distinguished professors at elite universities — the implicit assumption that tax revenues automatically move in the same direction as tax rates seem impervious to factual evidence.

I mean, come on. Don’t those guys read the WSJ’s op-ed page?

Sowell then considers the unintended consequences of several different types of social justice policies. First, in Sowell’s view, what politicians do is print money to provide “free” things to the public. “Then, as this additional money goes into circulation, the result is inflation.” On the next page, this thesis begins to unwind:

Sometimes a technical-sounding term —”QE2” — is used, to designate a second round of creating money. That sounds so much more impressive than simply saying “producing more money for politicians to spend.”

But, of course, QE2 (and QE1 and QE3 for that matter) did not result in significant inflation, despite confident conservative projections (including Sowell’s) that they would. Sowell does not reflect on this.

Sowell then discusses price controls (which we just covered!) He contends that they produce shortages (They sometimes do.) and notes the cynicism of Nixon, hardly novel contributions. But then he discusses minimum wage laws as a “special form of price control.” He complains:

Minimum wage laws are among the many government policies widely believed to benefit the poor, by preventing them from making decisions for themselves that surrogate decision-makers regard as being not as good as what the surrogates can impose through the power of government.

But what if it’s not just meddlesome third-party surrogates, but workers themselves demanding a minimum wage? Sowell doesn’t consider this possibility here, but his failure to do so will become more prominent in the following chapter, where we’ll address it in detail.

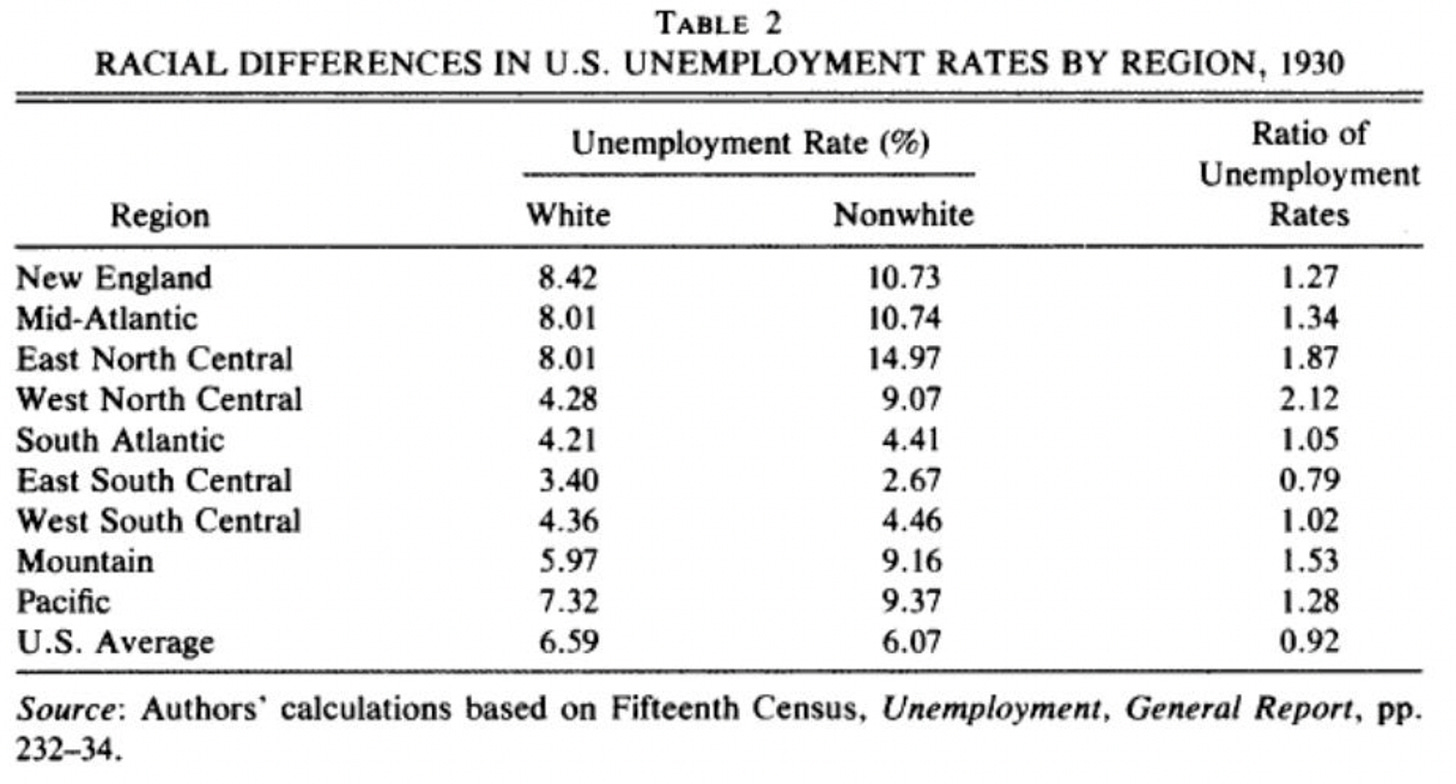

Sowell also blames minimum wage laws for racial disparities in unemployment, claiming “there were no significant racial differences in unemployment rates among teenage males in 1948.” Sowell says this is because the first minimum wage law took place in 1938 but its power was eroded away by inflation throughout the 1940s. However, following a series of minimum wage hikes in the 1950s the Black-white unemployment gap grew to a ratio of 2:1. We’ve covered this claim too. There was already a 2:1 unemployment gap between Black Americans and white ones in the North prior to minimum wage laws. That ratio was not apparent nationwide because a majority of the Black population lived in the South, home to much lower unemployment rates during the period under study. As Black Americans moved North, the 2:1 ratio became a national reality. Sowell says that this ratio can’t be the result of racism. After all “there was more racism then than today… A short, one-word answer [for why the disparity came into being] is economics.” In fact, a better one-word answer would be migration. Discrimination would work too.

Source:Vedder & Gallaway 1992

Sowell also approvingly cites Gary Becker’s thesis that the free market can eliminate discrimination and that, consequently, minimum wages laws disrupt that process because they “reduce the cost of discrimination to the discriminator.” Centuries of free-market economics in the North (and several decades in the South) didn’t bear this out regardless of whether the minimum wage was high or low. What did help was the Civil Rights Act, which is given one paragraph in the book that’s worth quoting in full:

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was an overdue major factor in ending the denial of basic Constitutional rights to blacks in the South. But there is no point trying to make that also the main source of the black rise out of poverty. The rate of rise of blacks into the professions more than doubled from 1954 to 1964. Nor can the political left act as if the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was solely their work. The Congressional Record shows that a higher percentage of Republicans than Democrats voted for that Act.

Even one of the most consequential pieces of legislation of the twentieth-century has to be relegated to an aside. I do not know if it would be fair to call the Act the “main source” for the Black rise out of poverty, but I think it was probably a necessary condition. It’s also amusing the gymnastics Sowell feels he needs to do to avoid the fact that conservatives did not support the Civil Right Act.

Sowell also contends that:

When there is no minimum wage law, or no effective minimum wage law, as in 1948, there is unlikely to be a chronic surplus of applicants.

This contradicts nearly the entire history of capitalism. In the few instances where there isn’t an available surplus, we hear cries from industry about a “labor shortage.” There is an economic historiography surrounding Say’s Law that contests that generalized crises wouldn’t happen but for minimum wages and other labor market regulations (and Sowell has written a book on this topic, which may be worth another post), but that theory has been widely discredited ever since the Great Crash of 1929. Even leaving crises aside, there’s usually some surplus labor sitting around.

The chapter concludes with a long exposition on why concerns over income inequality are unfounded. Sure, the “top 1%” are taking a greater share of American income. “But these are not the same people in the same brackets over the years.” And there’s some truth to this. As people get older, they acquire skills and experience and can usually get a better salary than their younger selves. But Sowell vastly overestimates the extent of economic mobility in the United States by cherry picking his sources. For instance, he notes that:

More than 50 percent of taxpayers in the bottom quintile moved to a higher quintile within ten years… [and] more than half of all American adults are in the top 10 percent of income recipients at some point in their lives.

These claims seem unbelievable, but they are technically true. However, Americans can temporarily move into a higher bracket for a single year by selling their home, receiving an inheritance, or withdrawing a large sum out of their retirement savings to meet an emergency. Even Sowell’s sources point this out. Here’s an excerpt from the abstract of one of the first papers Sowell cites:

The study findings suggest that many experience short-term and/or intermittent mobility into top-level income, versus a smaller set that persist within top-level income over many consecutive years.

Sowell then uses this to note that individuals in the top 1% “saw their incomes actually fall by 26 percent during the same decade [1996 to 2005].” Of course, if you sell your home one year and don’t the next, your income is likely to fall. Sowell gets close to recognizing this. When he’s arguing that the economy couldn’t possibly be rigged for the rich, he cites the fact that “71 percent of them [the top one percent] would not repeat their one year in that high income bracket during the 23 years covered by the Internal Revenue Service data.” Sowell thinks he’s providing evidence for our great economic mobility, but in fact he’s just pointing out that sometimes people sell valuable assets that it took them years to purchase. Half of Americans simply aren’t being paid a salary of $50,000 their whole lives except for a sudden raise to $180,000 for a single year. To think otherwise is preposterous. Once you recognize that economic mobility is not near as common as Sowell lets on, it once again becomes eminently reasonable to be concerned about widening income and wealth inequality.

Sowell also lambasts “income distribution alarmists” for their concerns over “supposedly “stagnating” income growth among Americans.” While household incomes have stagnated, households have also been shrinking in size and working less. And that’s a fair enough point (though it by no means successfully closes the question.) But it’s also true that median weekly real earnings for workers didn’t increase by a single penny between 1979 and 2014.

Source: Carpe Diem Blog

Source: FRED

Sowell then complains that:

In these data, official “poverty” means whatever these statisticians say it means. No more and no less.

Poverty is really no big deal, Sowell implies:

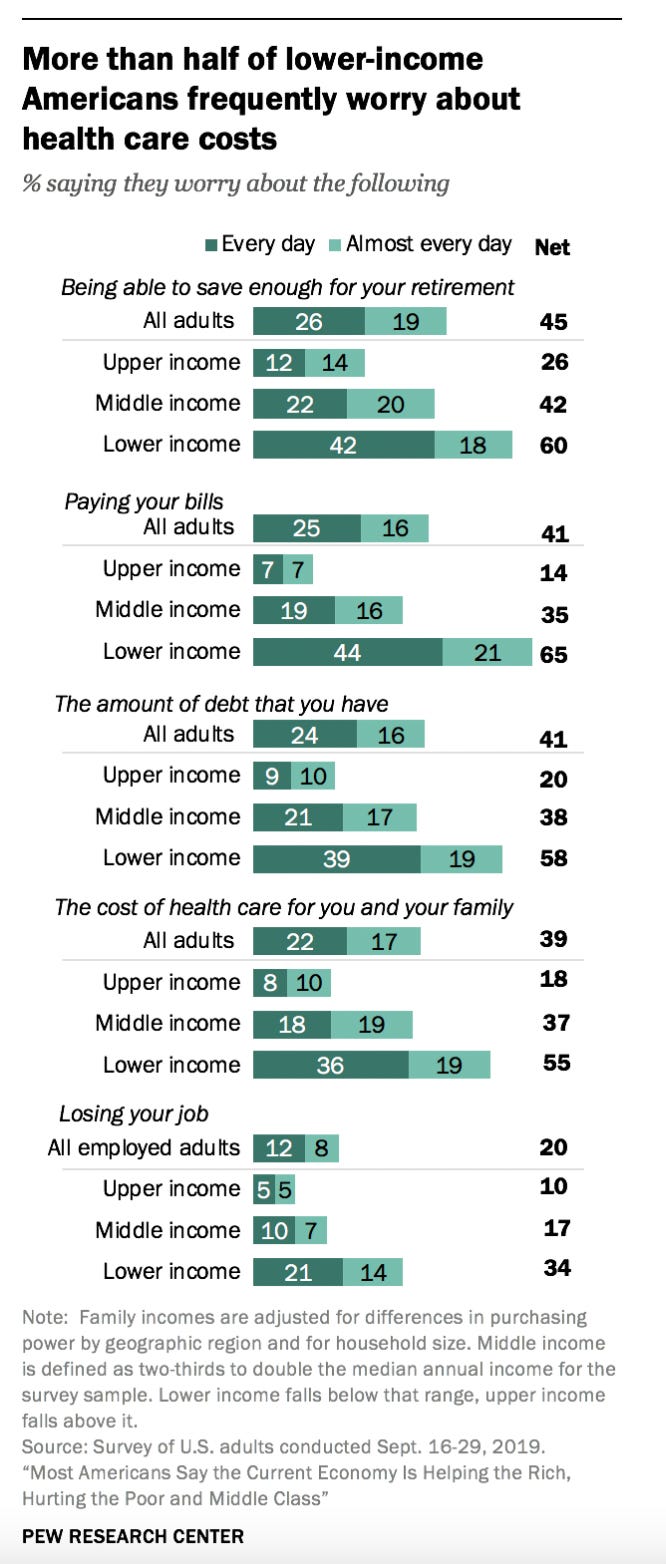

Ninety-seven percent of people in official poverty in 2001 had a color television… Seventy-three percent owned a microwave oven... [If the poor have any problems, they aren’t economic; they have] more serious and even urgent problems as victims of crime and violence than in the past… that [is] deserving long-overdue attention… than a supposedly “stagnating” income problem.

Source: Pew Research

Sowell does not appear to have consulted any poor people about this, and he surely isn’t drawing these conclusions based on polling of people in low-income brackets. But that’s a good segway into our next chapter, which is all about how elites assume they know what’s good for everyone else.

CH4: Knowledge Fallacies

This chapter opens with Sowell noting that:

Both social justice advocates and their critics might agree that many consequential social decisions are best made by those who have the most relevant knowledge. But they have radically different assumptions as to who in fact has the most knowledge.

Sowell contends that social justice advocates are a bunch of intellectual know-it-alls who believe themselves to be the possessors of all important knowledge, while Sowell takes a broader view:

Knowledge, however, does not exist in a simple hierarchy with the kind of special knowledge taught in schools and colleges at the top, and more mundane knowledge at the bottom. Some knowledge… is more consequential than other knowledge, and that varies with specific circumstances.

Sowell’s view of knowledge seems agreeable to me, so what implications does he draw from it. First, he criticizes the social justice advocates who want to enact policies for the good of other people:

It is not enough to say, as Professor Rawls said, that “society” should “arrange” to produce certain outcomes — somehow. The choices of institutional mechanism matter, not only from the standpoint of economic efficiency, but even more so for the sake of preserving the freedom of millions of people to make their own decisions about their own lives as they see fit, rather than have surrogate decision-makers preempt their decisions in the name of noble-sounding words such as “social justice.”

Of course, Rawls shared these concerns about the design of public institutions and addressed them throughout his work. Sowell also smacks down some other social justice advocates for their anti-democratic attitudes. Here’s a quick rundown:

William Godwin said the masses need elites as “guides and instructors'' to the people. Mill highlighted the importance of the “influence of a more highly gifted and instructed One or Few.” Walter Weyl’s “socialized democracy” restricted peoples’ ability to freely negotiate with employers by imposing labor laws. Rousseau’s “general will” was determined by leaders and gave them carte-blanche. Ronald Dworkin argued that “a more equal society is a better society even if its citizens prefer inequality.” And Marx’s quote that “The working class is revolutionary or it is nothing” was supposedly presenting the working class an ultimatum regarding its moral worth rather than its prospects for obtaining political power.

Sowell takes many of these sentence fragments out of context, but they do illustrate Sowell’s opposition to paternalistic Progressives. Instead, Sowell approvingly cites Hayek’s theorizing on knowledge which contends that nobody holds all knowledge in its totality and that “A fool can put on his coat better than a wise man can do it for him.”

But does this mean that Sowell supports democratic decision-making? One might think so, but it’s not at all clear. His inspiration, Hayek, had an ambivalent attitude toward democracy, often favoring dictators who implemented his preferred policy proposals, like Portugal’s Salazar and Chile’s Pinochet.

Sowell creates a black and white world, where either people decide for themselves or surrogates do. But where does democracy fit into this? Sometimes people elect surrogates that they clearly want to undertake certain actions on their behalf, or they vote on referendums. Sowell never mentions the possibility of people making democratic decisions, despite taking jabs at Progressives (most of whom are long dead) for expressing their contempt for democracy or the masses generally.

What if it’s not just some Progressive do-gooder, but the general public that wants a higher minimum wage? Sowell says that:

Minimum wage laws are another example of intellectual elites and social justice advocates acting as surrogate decision-makers…[that increases] the unemployment rate of black males.

But 89% of Black Americans want a $15 minimum wage. By his own logic, who is Thomas Sowell to tell them what’s good for them? We never get an answer to this. Instead, Sowell uses the rest of this chapter to scoff at some uppity Progressives, and he begins with an unintentionally funny anecdote:

Sowell begins by complaining about the Supreme Court “providing newly discovered “rights” for criminals” in the 1970s, including the new requirements that suspects in custody must be read their Miranda rights and that evidence must be legally seized to be admissible in court. He then tells us the following story:

At a 1965 conference of judges and legal scholars, when a former police commissioner complained about the trend of recent Supreme Court decisions on criminal law… a law professor responded with scorn and ridicule, [during which Justices] Warren and Brennan “frequently roared with laughter.”...A mere police official opposing learned Olympians of the law may have seemed humorous to elites at this gathering.

But Sowell’s telling of this anecdote was pieced together from a New York Times piece. If you read that piece, you’ll learn that the “mere police official” was no other than Michael J. Murphy, the recently retired New York City Police Commissioner who had spent the last year violently crushing riots in Harlem and fighting tooth-and-nail to prevent citizens from establishing a civilian oversight board to punish police brutality. In the conference Sowell is discussing, Murphy described the people he encountered on the streets as “vicious beasts.” It’s a good thing Murphy isn’t a Progressive intellectual; otherwise he might have caught some flak from Sowell for a comment like that. (The New York Times story in its entirety is shocking for its similarities to contemporary debates around criminal justice. For that reason, I’m attaching a screenshot of the archived article.)

Source: NYT

Sowell also spends some time upset at those who want to regulate the payday lending industry and those who believe that children should be taught sex education. The anecdotes don’t have the same humor as the first one. They cite a change in policy (limiting interest rates on payday loans, teaching children sex education, or investing in urban renewal) and cite somebody upset with it. Public opinion or the good of society (or any segment of it) is irrelevant. If Sowell can find one person that’s unhappy, then the mere fact that the project is not Pareto-optimal is enough for him to condemn it.

Ch5: Words, Deeds, and Dangers

This chapter mostly repeats already-established points with slightly different examples. Instead of talking about incompetent minority pilots, for example, we now talk about incompetent minority generals:

A country fighting for its life, on the battlefield, cannot afford the luxury of choosing its generals on the basis of demographic representation.

We’re reminded again that nobody has access to the totality of useful knowledge and that we should remain humble in the face of that reality. And you know who really isn’t humble? That’s right, social justice advocates. This chapter mostly consists of unsubstantiated complaints about them (again, without citing them.) Social justice advocates pay “little attention to places where the poor have risen out of poverty.” They think people are too stupid to make their own decisions. They are dogmatic and reject all criticism. You get the idea. Sowell laments that:

Today it is possible, even in our most prestigious educational institutions at all levels, to go literally from kindergarten to a Ph.D. without ever having read a single article — much less a book — by someone who advocates free-market economies or who opposes gun control laws.

This seems dubious, but it fits with Sowell’s characteristic style of pretending he’s delivering some economic forbidden fruit, rather than the typical stuff peddled out of mainstream economics departments since at least the 1980s.

Sowell does insert a little new material. He analogizes racism to a disease, saying:

We certainly cannot simply ignore the disease and hope for the best… [Challenging it can be difficult as] racists do not publicly identify themselves.

However, “people who have incentives to maximize fears of racism include politicians seeking to win votes… It is by no means certain whether the enemies of American minorities are able to do them as much harm as their supposed “friends.””

Yes, this is the only time the potential negative effects of racism on minority outcomes is examined, and it’s only to wave it away and suggest that anti-racists are probably actually worse. After all, “If racists cannot prevent today’s minority young people from becoming pilots, the teachers unions can — by denying them a decent education.” You might wonder if Sowell ever mentions any other factors that might disproportionately keep young Black Americans from a quality education. He does not.

Sowell also attacks affirmative action. He begins by noting Kennedy’s 1961 executive order that implemented a form of affirmative action that was essentially equivalent to equal opportunity (not what normal people think of when they hear the phrase “affirmative action” today.) But, Sowell reports:

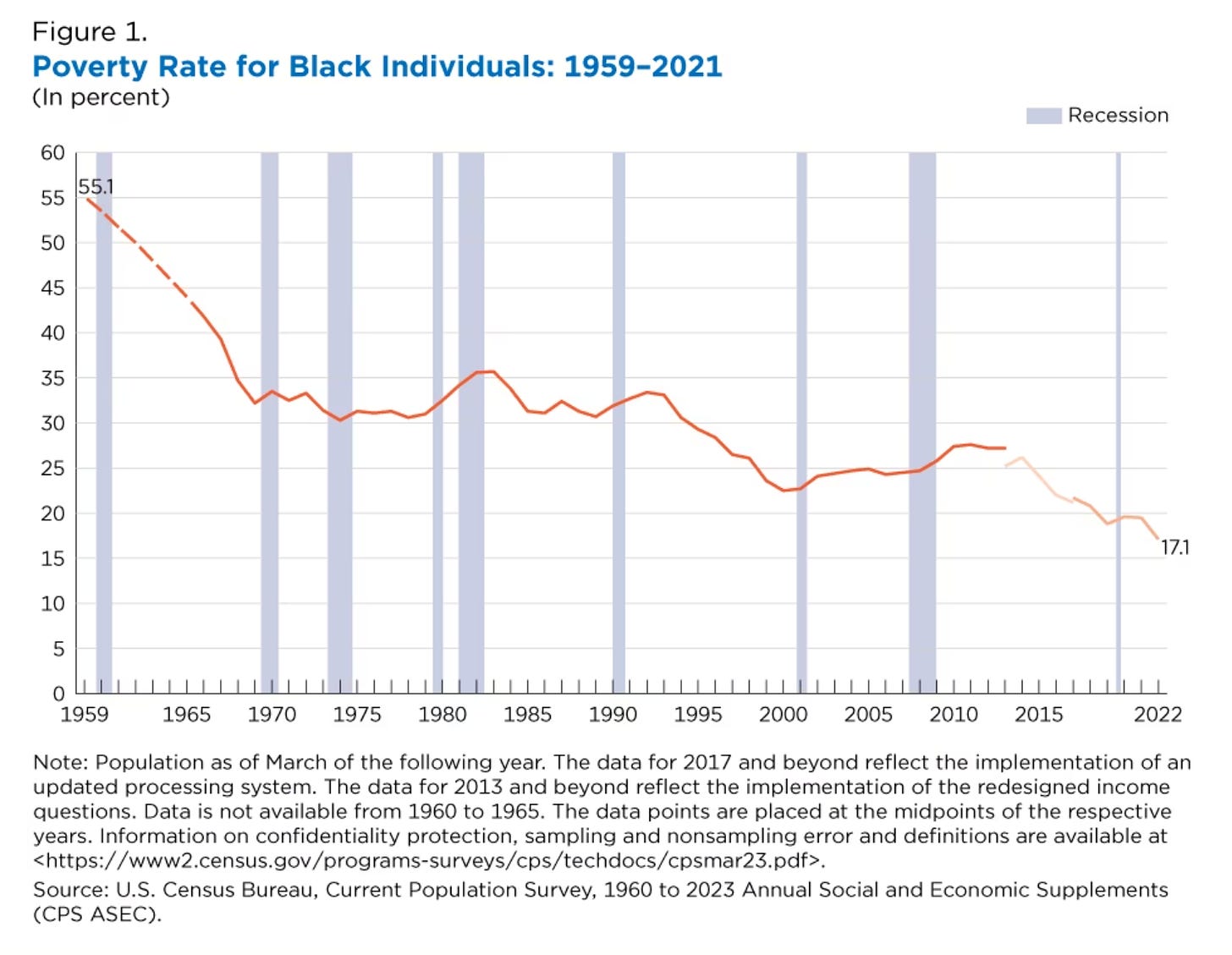

Subsequent Executive Orders by Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon made numerical group outcomes the test of affirmative action by the 1970s. With affirmative… it was widely regarded as axiomatic that this would better promote their progress in many areas. But, the one-percentage-point decline in Black poverty during the 1970s, after affirmative action meant group preferences or quotes goes completely counter to the prevailing narrative.

This sounds compelling, but the truth is hidden behind the phrase “by the 1970s.” The “group outcomes” test Sowell reviles took effect after an LBJ Executive Order in 1965. In the years immediately following, Black poverty witnessed one of its steepest declines ever. It’s well possible that this could have been due to factors other than LBJ’s executive order, but since Sowell’s primary debunking technique involves looking for mere correlations, he might not know how else to explain that progress away.

Source: US Census

Sowell also seems to blame the war on poverty for the 1968 uprisings:

The massive ghetto riots across the nation began during the Johnson administration… The riots subsided after that administration ended, and its “war on poverty” programs were repudiated.

Again, Sowell relies on nothing but correlation, but he’s not alone in arguing that the riots broke out because Black people were given too much. A more thoughtful analysis of why these riots took place comes from MLK’s “The Crisis in America’s Cities,” which happens to have some more thoughtful comments on discrimination and racial disparities too. Here’s its opening paragraph:

A million words will be written and spoken to dissect the ghetto outbreaks, but for a perceptive and vivid expression of culpability I would submit two sentences written a century ago by Victor Hugo:

“If the soul is left in darkness, sins will be committed. The guilty one is not he who commits the sin, but he who causes the darkness.”

The policy makers of the white society have caused the darkness; they created discrimination; they created slums; they perpetuate unemployment, ignorance and poverty. It is incontestable and deplorable that Negroes have committed crimes; but they are derivative crimes. They are born of the greater crimes of the white society. When we ask Negroes to abide by the law, let us also declare that the white man does not abide by law in the ghettos. Day in and day out he violates welfare laws to deprive the poor of their meager allotments; he flagrantly violates building codes and regulations; his police make a mockery of law; he violates laws on equal employment and education and the provisions for civic services. The slums are the handiwork of a vicious system of the white society; Negroes live in them but do not make them any more than a prisoner makes a prison.

Conclusion

While the world has changed a lot since 1968, we still enjoy the inheritance of past generations. Those slums MLK mentioned are still standing. Unemployment, ignorance, and poverty are all still perpetuated, primarily against the same groups of people they have been for centuries. That’s not always because people actively choose to discriminate. Structural inequality, implicit biases, and the mere stickiness of the past can keep past disparities in place for entirely arbitrary reasons. Sowell shrugs his shoulders, contending that arbitrariness is merely part of life, even if it’s anathema to any common sense understanding of the phrase “equal opportunity.”

Sowell’s contention in this book is that it’s fallacious to disagree with his free-market fundamentalism. If you merely mention the role of discrimination or slavery in shaping market outcomes, Sowell stands ready to accuse you of reductionism. If you think the rich should be taxed, Sowell will explain to you that people are not chess pieces, though he won’t touch the economic literature on such a topic. If you promote raising the minimum wage, you’re a social justice do-gooder with no appreciation for the knowledge of affected parties. Who cares if those affected parties agree with you? Thomas Sowell has a repertoire of Wall Street Journal op-eds, neo-Confederates, and Hayek quotes ready to tell you that you’re a hubristic and dogmatic intellectual following in the intellectual tradition of a bunch of eugenicists.

That would be a problem if this book were trying to convince anybody. After reading it, I am confident that it’s not. Sowell does not even bother to cite the contemporary “social justice advocates” that he is taking on, instead choosing to rip sentence fragments out of the works of the dead. The only living adversary he addresses by name is Ralph Nader, and that’s only by mentioning in passing a quote from an article Nader published in 1959. The reader, who presumably already sees it Sowell’s way, is expected to fill in these gaps or merely assume that Sowell’s adversaries think in the ways he says they do. Nor is this work a piece of scholarship. Sowell provides several pages of endnotes, which at times span an impressive scope of economic history. But he frequently misrepresents his sources and for each time he cites Braudel, he then turns around and mischaracterizes an op-ed. Thomas Sowell is convinced that the dogmatic eggheads, armed with their insular studies, are foisting their policies on us in an ill-conceived attempt to make the world a better place. To compensate, Sowell dogmatically persists in his belief that public policy should never do anything to improve the world, and that we should all quiet down and leave the rich to run the affairs of society.

Thank you for reading! If you got this far, please consider subscribing.

Thanks for the detailed review.

With any book written for public consumption, most of the arguments are simplifications in one way or another, but I think the alternatives to Sowell's arguments are probably more misleading simplifications. Sowell at least gets at something that is actually true - market mechanisms work better than alternatives, delivering on innovation and growth (growth enables human cooperation, which is otherwise a tenuous proposition). Diatribes about the problems of inequality or poverty that plead for mitigation offer little in the way of bonafide solutions (it isn't like many things haven't been tried). Part of the reason for this is that the contra-Sowell position often misunderstands the nature of "structural inequality" and stickiness of the past (btw Phil Tetlock's work has shown there is little-to-no test-retest validity nor explanatory power in IAT so I'm setting that aside).

For a little bit about the potent forces of inequality, I recommend checking out Greg Clark's work on social mobility. Essentially, social mobility is an almost fixed constant across in human societies (his observation travels to other societies surprisingly well), and relative patterns of stratification are remarkably durable for reasons that are probably hard to modify (see --> https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.2300926120).

Thank you for a breakdown of Sowell's recent book. Very helpful when to have all the citations and quotes.

I've read other works by Thomas and watched a number of interviews. He's a thoughtful, intelligent person and put in long work. However as you've noted, his cherry picking and omission of information is there to suit the narrative and this persona he created; that is a Black Conservative Capitalist Contrarian. It makes him unique in a sea of white conservatives and gives him special status in that group.

It's unfortunate his almost dogmatic adherence to conservative, capitalists ideologies has lead him down this path. I think he could have benefited society as a whole to a much greater extent had he been more flexible in his analysis of societal economic structures.